With Oscar night fast approaching, it’s time to hand out my own awards for the past movie year. As always, only films with an imdb date of 2010 are eligible, which means this will include a lot of films that haven’t been released theatrically in the US yet.

These are the nominees, I’ll have the winners up on Monday, to compare with the Oscar winners. For my Oscar predictions, check out the Metro Classics website.

Best Picture:

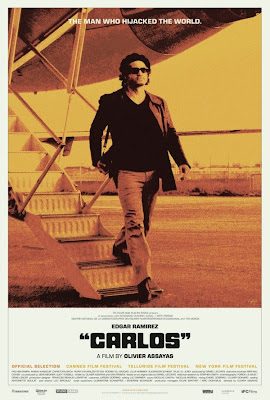

1. Carlos

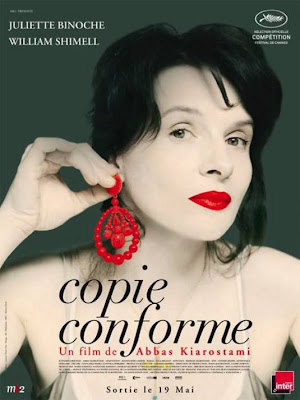

2. Certified Copy

3. Exit Through the Gift Shop

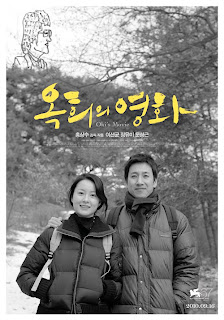

4. Oki’s Movie

5. Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives

Best Director:

1. Olivier Assays, Carlos

2. Abbas Kiarostami, Certified Copy

3. Hong Sangsoo, Hahaha & Oki’s Movie

4. Joel & Ethan Coen, True Grit

5. Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Uncle Boonmee

Best Actor:

1. James Franco, 127 Hours

2. Edgar Ramirez, Carlos

3. John Chang, The Drunkard

4. Leonardo DiCaprio, Shutter Island & Inception

5. Jesse Eisenberg, The Social Network

Best Actress:

1. Natalie Portman, Black Swan

2. Hailee Steinfeld, True Grit

3. Juliette Binoche, Certified Copy

4. Yun Junghee, Poetry

5. Emma Stone, Easy A

Supporting Actor:

1. Christoph Bach, Carlos

2. Teddy Robin, Gallants & Merry Go Round

3. Mark Ruffalo, The Kids are All Right & Shutter Island

4. Kieran Culkin, Scott Pilgrim vs. the World

5. John Hawkes, Winter’s Bone

Supporting Actress:

1. Wei Wei, The Drunkard

2. Olivia Williams, The Ghost Writer

3. Greta Gerwig, Greenberg

4. Rosamund Pike, Made in Dagenham

5. Rooney Mara, The Social Network

Original Screenplay:

1. Olivier Assayas, Dan Franck & Daniel Leconte, Carlos

2. Abbas Kiarostami, Certified Copy

3. Zhu Wen, Thomas Mao

4. Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Uncle Boonmee

5. Hong Sangsoo, Oki’s Movie & Hahaha

Adapted Screenplay:

1. Freddie Wong, The Drunkard

2. Sylvain Chomet, The Illusionist

3. Catherine Breillat, The Sleeping Beauty

4. Aaron Sorkin, The Social Network

5. Joel & Ethan Coen, True Grit

Foreign Language Film:

1. Carlos

2. Certified Copy

3. Oki’s Movie

4. Thomas Mao

5. Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives

Documentary Feature:

1. Exit Through the Gift Shop

2. I Wish I Knew

3. Get Out of the Car

4. Sweetgrass

5. Strange Powers

1. The Illusionist

2. Toy Story 3

Film Editing:

3. Carlos

4. Exit Through the Gift Shop

5. Shutter Island

Cinematography:

1. Matthew Libatique, Black Swan

2. Denis Lenoir & Yorick Le Soux, Carlos

3. Luca Bigazzi, Certified Copy

4. Jeff Cronenweth, The Social Network

5. Roger Deakins, True Grit

Art Direction:

1. Carlos

2. Certified Copy

3. Shutter Island

4. Scott Pilgrim vs. the World

5. Uncle Boonmee

Costume Design:

1. Carlos

2. Certified Copy

3. The Sleeping Beauty

4. The Social Network

5. True Grit

Make-up:

1. 127 Hours

2. Black Swan

3. Shutter Island

1. 127 Hours

2. Black Swan

3. Shutter Island

4. The Social Network

5. Scott Pilgrim vs. the World

Sound Editing:

1. Kick Ass

2. Scott Pilgrim vs. the World

3. Shutter Island

4. Toy Story 3

5. True Grit

Visual Effects:

1. 127 Hours

2. Inception

3. Gallants

4. Predators

5. Scott Pilgrim vs. the World

Original Score:

1. 127 Hours

2. The Illusionist

3. Never Let Me Go

4. The Social Network

5. True Grit

Soundtrack:

1. Black Swan

2. Carlos

3. Shutter Island

4. Strange Powers

5. Scott Pilgrim vs. the World

See the post below for the nominees:

See the post below for the nominees: