/Film has some stills up from Wong Kar-wai’s latest film My Blueberry Nights, which kicks off the Cannes Film Festival this week.

Movie Roundup: Beaned Again Edition

Fallen behind again, thanks to yet another cold. So, as word breaks that the A’s have acquired former Mariner folk hero Chris Snelling, I’ll drown my sorrows with my brand-new copy of Conan The Barbarian and try to kick out a quick-hit version of the roundup. This is Part One, which I wrote on Wednesday but am only getting around to posting now. Part Two will follow later this week, hopefully.

Fallen behind again, thanks to yet another cold. So, as word breaks that the A’s have acquired former Mariner folk hero Chris Snelling, I’ll drown my sorrows with my brand-new copy of Conan The Barbarian and try to kick out a quick-hit version of the roundup. This is Part One, which I wrote on Wednesday but am only getting around to posting now. Part Two will follow later this week, hopefully.

Lancelot du lac – Robert Bresson’s version of the end of Camelot has essentially the same plot as the godawful First Knight (#86, 1995): Lancelot returns to Camelot after the failed grail quest, tries not to sleep with Guinevere, fails and the whole thing falls apart. However, Bresson takes the opposite route to filming a medieval epic. Instead of overblown melodrama, Bresson made a minimalist epic, consisting of little dialogue, his typically emotionless acting and a camera that willfully avoids showing the most obvious images of a scene in favor of sounds (hoofbeats in particular), and lingers longer than it has any right to over apparently inconsequential things (the knights’ unarmored legs being a particular favorite). Like all the Bresson’s I’ve seen, it unnerves you, defies your expectations and provides a wholly unique experience. The #6 film of 1974.

Wild Strawberries – Somehow I missed this when I saw it a few months ago, but frankly I was underwhelmed. The dream sequence was pretty cool, but other than that, this quite famous roadtrip movie about about an old professor traveling the countryside and flashbacking on his life (think Deconstructing Harry, without the jokes) just left me cold. The #10 film of 1957.

Metropolis – Fritz Lang’s hugely influential mashup of the Communist Manifesto and the Tower Of Babel is perhaps the most influential sci-fi film of all-time. Tremendously expensive in its time, it set the template and standard for the way we think of the filmed future (Blade Runner’s only the most obvious example of it’s influence). As a movie though, it’s got some serious flaws: a whiny protagonist, some obvious plot holes (complicated perhaps by the incomplete nature of the most recent restoration, though Lang’s Dr. Mabuse, The Gambler had the same problem), and the interesting thematic choice of resolving the eternal struggle of rich and poor through a damsel in distress love story rescue.

The Long Voyage Home – John Ford’s adaptation of a quartet of Eugene O’Neill plays set on board a ship near the beginning of World War 2. Shot by Gregg Toland not long before he did Citizen Kane, it’s got the same brilliant deep-focus black and white photography. Terrific performances from Ford’s regulars (Ward Bond, Thomas Mitchell, John Wayne, etc) liven the generally dour material.

They Were Expendable – Much to his distress, John Ford was pulled out of the war to shoot this propaganda film about the guys who proved the usefulness of PT boats in waging war during the battle for The Philippines at the start of WW2. As war films go, it’s pretty great, with top notch performances from John Wayne and Robert Montgomery, some really nice scenes with Donna Reed, and some exciting action sequences.

8 Women – François Ozon’s musical murder mystery stars three generations of hot French women, some of whom can actually sing. They’re all gathered one winter eve only to learn that the family patriarch has been murdered. Cut-off from the outside world, it’s up to them to solve whodunnit, airing all their dirty secrets and essentially exposing themselves as the most screwed up family you’ll ever see. And all with a solo musical interlude for each actress. Stars Catherine Deneuve, Danielle Darrieux, Isabelle Huppert, Emmanuelle Beart, Fanny Ardant and Ludvine Sagnier. My first Ozon film, but it won’t be the last. The #5 film of 2002.

The Informer – Tag Gallagher ripped on this a lot in his great book John Ford: The Man And His Films, though I liked it quite a bit. Gallagher didn’t like the lack of tonal variance (all-serious, all the time), whereas I enjoyed the atmospheric, proto-noir, hyper-foggy images, and found plenty of humor and sympathy in Victor McLaglen’s portrayal of a desperately poor former IRA operative who turns his old buddy into the police for the reward money. Sure, it doesn’t rank with Ford’s greatest films, but it’s in the next tier.

The Wings Of Eagles – Another Ford film, this one a biopic about naval aviator turned paralyzed screenwriter Spig Wead. Wead and Ford were friends, and it shows in this rather tame film. Sure, Wead has his bad qualities, but he’s still a helluva guy. Ward Bond does a hilarious Ford imitation as the Hollywood director Wead goes to work for, and like all Ford films, there are some really terrific moments, but they’re way too few and far between. The #11 film of 1957.

A Scanner Darkly – Richard Linklater’s interpolated rotoscope adaptation of a Philip K. Dick mindbender is perhaps the best Dick adaptation ever (yes, that includes Blade Runner). The fluid, squggly animation is perfect to the shifting realities of Dick’s druggy, schizophrenic worldview. Keanu Reeves plays an undercover cop who loses his identity in his job (thanks to a killer new drug) and begins to suspect reality is even more fucked-up than it appears when you’re high. Also stars famous druggies Robert Downey Jr, Woody Harrelson and the sorely missed Winona Ryder. The #4 film of 2006.

Rome, Open City – Roberto Rossellini’s breakthrough film, and the movie that launched Italian neo-realism, shot with whatever the crew could find around town in the middle of a war. A story of the Italian Resistance during WW2, it builds to a devastating climax halfway through the film, such that everything that follows is, well, anti-climactic (much like Full Metal Jacket). Still, unlike, say Metropolis, it manages to be both stylistically influential and a tremendous film of its own. I’m not a big fan of neo-realism, at least, I didn’t like Bicycle Thieves, but this was great.

Rome, Open City – Roberto Rossellini’s breakthrough film, and the movie that launched Italian neo-realism, shot with whatever the crew could find around town in the middle of a war. A story of the Italian Resistance during WW2, it builds to a devastating climax halfway through the film, such that everything that follows is, well, anti-climactic (much like Full Metal Jacket). Still, unlike, say Metropolis, it manages to be both stylistically influential and a tremendous film of its own. I’m not a big fan of neo-realism, at least, I didn’t like Bicycle Thieves, but this was great.

How Green Was My Valley – The last of my Gallagher-inspired Ford marathon is this story of a Welsh coal mining town that famously beat Citizen Kane for the best picture Oscar. It’s a fine film, with some wonderfully lyrical sequences (Maureen O’Hara’s wedding, Roddy McDowell digging for his father) but after a single viewing I don’t think it’s the masterpiece Gallagher describes in his book. I don’t know if he was overcompensating for the film’s subsequent overshadowing by Kane, or if I just missed the many, many subtleties he found in the film. Perhaps a little of both.

House Of Yes – Parker Posey gives a fine performance as a crazy rich girl in an incestuous relationship with her brother (Josh Hamilton from Kicking And Screaming) in this decent enough pice of filmed theatre. Tori Spelling(!) plays Hamilton’s appalled fiancée and Freddie Prinze Jr his younger brother. The #40 film of 1997.

The Trouble With Harry – Essentially Alfred Hitchcock’s version of Weekend At Bernies, as a collection of eccentrics (including Shirley Maclaine and Jerry Mathers) in a small New England town discover, bury, exhume, and rebury (again and again) a dead body. Quirky and entertaining, with a marvelous sense of place. It’s light Hitchcock, and a lot more fun than the similarly weightless To Catch A Thief. The #12 film of 1955.

Coconuts – The first true Marx Brothers film is also the worst one I’ve ever seen. There are some classic jokes, and some funny Busby Berkeley-esque dance sequences, but there’s way too many lame songs sung seriously by non-Marxes.

Woman In The Dunes – Hiroshi Teshigahara’s beautiful, mysterious and odd little film zigged when I was certain it was going to zag, almost always a pleasant experience. A high school science teacher on vacation to study some bugs in a desolate desert gets tricked into living in a deep, inescapable sand hole with an odd, and not unattractive, widow who wants to ‘marry’ him. I was prepared for an intense Japanese ghost story along the lines of Kwaidan or Ugetsu, instead it’s naturalistic and more than a little political allegory. Lyrical and kinky, it looks a little like Resnais’s Hiroshima mon amour with sand. The #7 film of 1964.

Woman In The Dunes – Hiroshi Teshigahara’s beautiful, mysterious and odd little film zigged when I was certain it was going to zag, almost always a pleasant experience. A high school science teacher on vacation to study some bugs in a desolate desert gets tricked into living in a deep, inescapable sand hole with an odd, and not unattractive, widow who wants to ‘marry’ him. I was prepared for an intense Japanese ghost story along the lines of Kwaidan or Ugetsu, instead it’s naturalistic and more than a little political allegory. Lyrical and kinky, it looks a little like Resnais’s Hiroshima mon amour with sand. The #7 film of 1964.

2 Or 3 Things I Know About Her – One of Jonathan Rosenbaum’s favorite Jean-luc Godard films, I found it more of a way station between the Godard highlights Pierrot le fou and Week End: absurdist and comically self-referential like the first; logorrheic and blatantly political like the second. The plot setup is essentially the same as Buñuel’s Belle de jour: middle-class housewife is a prostitute in her spare time, but it’s more a slice of French life in the late 60s than an actual story. The #7 film of 1967.

The Loyal 47 Ronin – Kenji Mizoguchi’s two-part adaptation of the classic Japanese story (think their version of The Gunfight At The OK Corral or the Omaha Beach landing) is a masterpiece of action withheld. Through its nearly four hour running time, there’s almost no scenes of violence, including none of the many many ritual suicides that punctuate the story. Clearly what Mizoguchi’s after is not the action violence of a great revenge epic as the titular ronin seek to avenge their lord who was forced to kill himself after insulting a venal superior. Instead, he examines the culture and society that leads to a world in which mass suicide is the greatest possible act of honor. Filled with his signature long tracking shots, his camera constantly cranes over walls following the characters from above and thereby exposing and transcending the boundaries they choose to live in.

The Mizoguchi Movies I’ve seen, and all are great:

1. Ugetsu

2. Sansho The Bailiff

3. Story Of The Last Chrysanthemums

4. The Loyal 47 Ronin

5. Sisters Of Gion

6. The Life Of Oharu

7. Street Of Shame

Quote Of The Day

As reported on David Bordwell’s blog (see link on the sidebar), Werner Herzog speaking at Ebertfest:

“Our technological civilization is not sustainable on this planet. Nature is going to regulate us very quickly. . . . We’ll be the next ones [to go extinct]. But that’s okay. Let’s enjoy movies and friendship and beer.”

Prose Of The Day

From “Tender Buttons” by Gertrude Stein:

A light in the moon the only light is on Sunday. What was the sensible decision. The sensible decision was that notwithstanding many declarations and more music, not even notwithstanding the choice and a torch and a collection, notwithstanding the celebrating hat and a vacation and even more noise than cutting, notwithstanding Europe and Asia and being overbearing, not even notwithstanding an elephant and a strict occasion, not even withstanding more cultivation and some seasoning, not even with drowning and with the ocean being encircling, not even with more likeness and any cloud, not even with terrific sacrifice of pedestrianism and a special resolution, not even more likely to be pleasing. The care with which the rain is wrong and the green is wrong and the white is wrong, the care with which there is a chair and plenty of breathing. The care with which there is incredible justice and likeness, all this makes a magnificent asparagus, and also a fountain.

Movies Of The Year: 1954

It’s been too long, but here we go back to the countdown. Caveats, methodologies and all previous years, with the addition of any films I’ve seen since the original entries, can be found at The Big List, now in two parts!

It’s been too long, but here we go back to the countdown. Caveats, methodologies and all previous years, with the addition of any films I’ve seen since the original entries, can be found at The Big List, now in two parts!

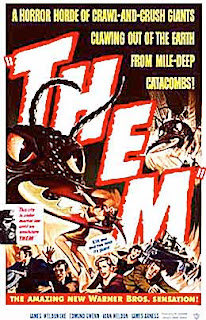

16. Them! – Giant ants attack a city in a classic 50s sci-fi Cold War parable (the ants are caused by nuclear tests in the desert.) The only time I saw this was on TV as a kid, but I still have an irrational fear of insects.

15. 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea – Live-action Disney sci-fi film about an obsessive captain, his submarine and the giant squid that attacks it. Cheesy special effects and aimed at an audience of kids, but it’s got Kirk Douglas and James Mason, and was directed by Richard Fleischer, who had one interesting career. From cheap but great noir (The Narrow Margin, His Kind Of Woman), to big budget crap (The Jazz Singer, Dr. Dolittle, Tora! Tora! Tora!) to B-movie wallowing (Fantastic Voyage, Soylent Green, Red Sonja), he was all over the auteurist map.

14. Dragnet – Essentially just an overlong episode of the TV series, but in Technicolor. Jack Webb’s just the facts procedural is a fine genre exercise, but it’s lacking in visual style. Compared to a procedural like Jules Dassin’s The Naked City, which tells a similarly straight story but with an expressive noir pallet, Webb’s brightly colored and evenly light LA comes off as drab and boring.

13. The Caine Mutiny – Filmed theatre of the well-acted variety, with Humphrey Bogart as the martinet commander of a naval vessel whose crew rebels during World War 2. Bogart’s great as the tightly wound, possibly insane Captain, but the crew comes of just as bad (especially that weasel Fred MacMurray). Also stars José Ferrar, Van Johnson and Lee Marvin, and directed by Edward Dmytryk (Murder, My Sweet, Back To Bataan) who was one of the Hollywood Ten who backtracked after being thrown in prison and named names.

12. Track Of The Cat – Very interesting William Wellman film about a family on a remote, snow-covered mountain. A panther of some type has been attacking their animals, so two of the sons (including Robert Mitchum) try to kill it. When the panther kills his brother, Mitchum sets off alone to find it. Meanwhile, the crises sets off a series of domestic squabbles at home, between the parents, the daughter and the third son, and the neighbor girl he wants to marry. Half low-key, yet intense, theatrical melodrama, half outdoor adventure film, Wellman shot the whole thing in pseudo black and white: it’s in color, but only a few key items are not black or white. It’s like Day Of Wrath meets Grizzly Adams. An odd film, and worth a second viewing.

12. Track Of The Cat – Very interesting William Wellman film about a family on a remote, snow-covered mountain. A panther of some type has been attacking their animals, so two of the sons (including Robert Mitchum) try to kill it. When the panther kills his brother, Mitchum sets off alone to find it. Meanwhile, the crises sets off a series of domestic squabbles at home, between the parents, the daughter and the third son, and the neighbor girl he wants to marry. Half low-key, yet intense, theatrical melodrama, half outdoor adventure film, Wellman shot the whole thing in pseudo black and white: it’s in color, but only a few key items are not black or white. It’s like Day Of Wrath meets Grizzly Adams. An odd film, and worth a second viewing.

11. A Star Is Born – The version with Judy Garland and James Mason isn’t as good as the one with Fredric March and Janet Gaynor, but it’s still pretty good. Mason’s the celebrity actor with a drinking problem that only becomes worse when the young wannabe he discovers and marries becomes more successful than him. Compared to the earlier version, directed by William Wellman, this George Cukor film is rather boated, especially by the addition of some mediocre Judy Garland songs (the songs are mediocre, not Judy, naturally. She’s as great as ever.)

10. Samurai I: Musashi Myamoto – The kind of samurai film Akira Kurosawa spent much of his career deflating, this first part of a biopic trilogy of Japan’s greatest samurai hero is full of colorful scenery and costumes, features a great performance by the always great April Fool Toshiro Mifune and was directed by Hroshi Inagaki in a reverential, if uninspiring style. It’s going to be on TV in a day or two, I’m a-gonna watch it again and see if it’s improved any in the decade or so since I last saw it.

9. The Far Country – One of the several dark Westerns directed by Anthony Mann starring James Stewart. Stewart plays a loner driving cattle across Alaska who becomes embroiled, very much against his will, in a dispute between a gang of criminals and the small town they control through violence and fear. This is similar to the character Stewart plays in the other Mann films: anti the typical Western hero, whose sense of duty and honor obliges him to protect the innocent. Instead, Stewart is a selfish jerk, only concerned with his own interests and avoiding conflict not for some non-violent ideal (as Stewart did in Destry Rides Again) but out of pure apathy for the public good. Being a Western, of course, this anti-hero eventually comes to protect civilization, but it’s a long struggle to get him there. The genre conventions are preserved, but the sense of post-war alienation is the dominant emotion, not the visceral excitement of the triumph of imperialism.

8. The Barefoot Contessa – Beautiful counterpart to Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s masterpiece All About Eve. Where that film was all cattiness and ambition in the world of Broadway actors, writers and directors, this film is wistful nostalgia and innocence corrupted by Hollywood, romanticism destroyed by cynicism. Humphrey Bogart gives one of his better performances as a run-down director who discovers Ava Gardner in Spain and watches her rise to stardom and tragic collapse as a result of love gone horribly wrong.

7. Dial M For Murder – Ray Milland plots to kill his wife, Grace Kelly, but has to improvise when she manages to fight off and kill the man he hired to murder her in this elegant little suspense film from Alfred Hitchcock. This is Hitchcock in his light, entertaining mode, despite, you know, the murder and everything. Milland is terrific as the scheming husband, sure of his own brilliance and Kelly’s as beautiful as ever. Made to be seen in 3D, I’ve only ever seen it on TV. I understand it’s much better with the silly glasses.

7. Dial M For Murder – Ray Milland plots to kill his wife, Grace Kelly, but has to improvise when she manages to fight off and kill the man he hired to murder her in this elegant little suspense film from Alfred Hitchcock. This is Hitchcock in his light, entertaining mode, despite, you know, the murder and everything. Milland is terrific as the scheming husband, sure of his own brilliance and Kelly’s as beautiful as ever. Made to be seen in 3D, I’ve only ever seen it on TV. I understand it’s much better with the silly glasses.

6. Sabrina – Speaking of charming, this is perhaps the great misanthrope Billy Wilder’s most ingratiating film, about a young girl, the daughter of the chauffeur, who loves the playboy son of her father’s employer. When she returns home from Paris she’s turned from a cute little wallflower into Audrey freakin’ Hepburn. The flighty son falls for her, as does his strictly business older brother, played by Humphrey Bogart at his fussiest. Sweet and romantic, and more than a little silly, I can’t imagine why anyone would ever want to remake it.

5. La Strada – The great Giulietta Masina stars in this Federico Fellini film about a young woman sold off by her family to be the wife of a traveling strongman, played by a dubbed-into-Italian Anthony Quinn. Quinn’s a brute who mistreats the poor girl at every opportunity. On their travels, they meet Richard Basehart, another circus performer, who treats the poor girl well enough to confuse her by explaining that Quinn, despite his boorishness, actually loves her. Masina is great, but the film feels to me like a warm up for Nights Of Cabiria (#3, 1957), in which she plays a similarly put upon character but with a more knowing, more existentially uplifting and moving impact.

4. On The Waterfront – A great example for the politics vs. art debate is this Elia Kazan film about longshoremen with a corrupt union in New York (or is it New Jersey?). Karl Malden plays the local priest who’s trying to get the workers to organize and inform on their mob boss union leaders so the government can lock them up. Marlon Brando plays an ex-prize fighter (Coulda been a contender) and brother of the boss’ right-hand man (Rod Steiger), who after falling for the ridiculously hot Eva Marie Saint starts to become morally confused and decides to talk to the feds. All of this is fine and moral, but for the fact that Elia Kazan named names to the House Un-American Activities Commision and this film was the defense of his actions. Like most Kazan films, the visual style is decent if unremarkable while the acting is phenomenal. Brando gives perhaps the finest performance by the greatest actor of his generation, and the other leads are at the top of their game as well. It’s a film I’ve seen maybe a dozen times, but I can’t bring myself to love it because of that rat Kazan.

3. Sansho The Baliff – Kenji Mizoguchi is perhaps the greatest filmmaker whose films remain largely unavailable on DVD (a situation which is slowly, finally, being remedied). I saw this years ago on video and thought it was one of the most depressing movies I’d ever seen. A few months later, I watched it in class and though it was one of the greatest movies I’d ever seen. Earlier this year, a traveling retrospective of Mizoguchi films played at Seattle’s Northwest Film Forum, and I got to see it a third time. While it’s not one of My Top 20 Movies, and right now only my third favorite Mizoguchi (after Ugetsu and The Story Of Late Chrysanthemums), it’s still a phenomenally great and powerful film, and, yes, one of the most depressing movies I’ve ever seen. A family of rich folks (mother and two kids) are on the way to their father’s new post in the country, when they’re kidnapped by slave traders. The mom is sold into a brothel and the two kids are trucked off to a slave labor camp, where they grow up battered and terrorized. A decade or so later they attempt to make their escape and reunite with their mother. Horrible things happen, hopes are dashed and yet humanity struggles on and many other great humanist themes. Like all Mizoguchi films, it’s shot in a beautiful black and white with long-take, long-shot tracking and crane shots that emphasize the reality of the hellish space the film depicts while simultaneously provoking a profound sense of aesthetic satisfaction. Criterion’s releasing it in a few months, I’ve already got my copy pre-ordered.

3. Sansho The Baliff – Kenji Mizoguchi is perhaps the greatest filmmaker whose films remain largely unavailable on DVD (a situation which is slowly, finally, being remedied). I saw this years ago on video and thought it was one of the most depressing movies I’d ever seen. A few months later, I watched it in class and though it was one of the greatest movies I’d ever seen. Earlier this year, a traveling retrospective of Mizoguchi films played at Seattle’s Northwest Film Forum, and I got to see it a third time. While it’s not one of My Top 20 Movies, and right now only my third favorite Mizoguchi (after Ugetsu and The Story Of Late Chrysanthemums), it’s still a phenomenally great and powerful film, and, yes, one of the most depressing movies I’ve ever seen. A family of rich folks (mother and two kids) are on the way to their father’s new post in the country, when they’re kidnapped by slave traders. The mom is sold into a brothel and the two kids are trucked off to a slave labor camp, where they grow up battered and terrorized. A decade or so later they attempt to make their escape and reunite with their mother. Horrible things happen, hopes are dashed and yet humanity struggles on and many other great humanist themes. Like all Mizoguchi films, it’s shot in a beautiful black and white with long-take, long-shot tracking and crane shots that emphasize the reality of the hellish space the film depicts while simultaneously provoking a profound sense of aesthetic satisfaction. Criterion’s releasing it in a few months, I’ve already got my copy pre-ordered.

2. Rear Window – One of the greatest, and most famous, of all Alfred Hitchcock films is this essay on voyeurism in which James Stewart plays a wheelchair-bound photographer who passes his convalescence watching his neighbors through their open windows. Not even the quite nubile Grace Kelly can manage to draw his attention away from the little dramas he invents for the people across the courtyard. Of course, this being Hitchcock, Stewart thinks he sees Raymond Burr kill his wife, and enlists Kelly and his nurse, Thelma Ritter, to help solve the mystery. As perverse as any Hitchcock film and one of the greatest metaphors for cinema ever filmed. It’s also a relentlessly entertaining suspense film. Few directors were as able to be both profound and popular at the same time as Hitchcock. Ford, Scorsese, Kubrick, Kurosawa, Renoir, Welles, Keaton, Chaplin, Hawks. . . .

1. The Seven Samurai – The greatest film ever made. The story is simple enough: poor farmers learn they’re going to be attacked by bandits, so they hire a group of samurai to defend them. Defenses are prepared, the bandits attack and life eventually goes on. Along the way, the whole realm of human emotion and community experience is chronicled, satirized, critiqued, and explored, with Kurosawa at the peak of his artistic powers. The film is huge, and not just in its running time (I find the film’s three and a half hours fly by faster than most 90 minute films). From that simple premise ideologies of book-length complexity grow through masterful, original, sometimes breathtaking, though often surprisingly subtle, technique. Dozens of characters are created and brought to life by some of the greatest actors of mid-century Japan, from stars Toshiro Mifune and Takeshi Shimura to minor character actors like Bokuzen Hidari and Seiji Miyaguchi.

1. The Seven Samurai – The greatest film ever made. The story is simple enough: poor farmers learn they’re going to be attacked by bandits, so they hire a group of samurai to defend them. Defenses are prepared, the bandits attack and life eventually goes on. Along the way, the whole realm of human emotion and community experience is chronicled, satirized, critiqued, and explored, with Kurosawa at the peak of his artistic powers. The film is huge, and not just in its running time (I find the film’s three and a half hours fly by faster than most 90 minute films). From that simple premise ideologies of book-length complexity grow through masterful, original, sometimes breathtaking, though often surprisingly subtle, technique. Dozens of characters are created and brought to life by some of the greatest actors of mid-century Japan, from stars Toshiro Mifune and Takeshi Shimura to minor character actors like Bokuzen Hidari and Seiji Miyaguchi.

It seems to be popular among the trendy critics of today to either dismiss or ignore Kurosawa in favor of his not-quite-contemporaries Mizoguchi and Ozu (as if there were a quota on how many Japanese directors are allowed into the Pantheon. Some of this criticism is an extension of the racist and xenophobic charges against him on both sides of the Pacific in decades past: that he was too Western and not “Japanese” enough. But largely the criticism now seems to be that he’s too popular, too simplistic and too epic compared to the intricate long takes of Mizoguchi and the simple family dramas and character studies of Ozu. Even the greatest critics occasionally fall victim to this misapprehension: my favorite film critic, Jonathon Rosenbaum, for example, includes only two Kurosawa films in his Top 1000 List (Ikiru and Rhapsody In August). Not surprisingly, Kurosawa’s being treated by the trendy today in the same way his idol (and most comparable director) John Ford was treated by critics before the auterists came along and showed how stupid everyone was being. Ford is now revered by critics good and bad, and I love his work as well. But I’d still take Kurosawa if I had to choose between them. There’s nothing Ford has that Kurosawa doesn’t.

Some good Unseen Films this year, but the first is the one I want to see most. I’m just barely getting into Roberto Rossellini, there’s a whole lot I need to see.

Voyage In Italy

Magnificent Obsession

Touchez Pas Au Grisbi

Broken Lance

French Cancan

Seven Brides For Seven Brothers

White Christmas

Godzilla

Brigadoon

Creature From The Black Lagoon

Animal Farm

The High And The Mighty

Suddenly

Wuthering Heights

Chikamatsu Monogatari

Johnny Guitar

Salt Of The Earth

Silver Lode

Senso

River Of No Return

Executive Suite

Adventures Of Hajji Baba

Siskel, Ebert, Protestants

This clip has been making its way through a series of tubes for the last several days, but if you haven’t seen it yet, do so. Courtesy of Sergio Leone And The Infield-Fly Rule.

Back In Tweed

Been a busy few weeks around here at The End Of Cinema HQ. I got flattened with a cold for a week, went on vacation for ten days and have been watching as much baseball as possible during opening week (melt damn snow!). I have managed to watch a few movies, but not too many (I still haven’t made it to Grindhouse, one of my most anticipated movies of the year). I anticipate getting back in the swing of things over the next couple of days, with a Movie Roundup and the next installment of the Movies Of The Year countdown, 1954. Can anyone guess what #1 from that year will be?

I’ve also been working on making The End Of Cinema a theatrical experience, trying to program an experimental repertory series at my theatre. We’re currently in negotiations with the execs at corporate headquarters, but it looks like we’re going to get the chance to try and make it work. Repertory cinema has died a slow death over the last 15 years, as the cost of prints, the plague of corporate multiplexes and fear of advanced technology (DVD and cable) have made suits wary of the effort required to try to market a rep series effectively, even in a film-crazy urban market like Seattle. But I and my coworkers think we can make it work at our theatre, and it looks like we’ll get the chance (knock wood).

We proposed an initial calendar of nine films, playing one day a week for nine weeks. Each film represents a decade of film history, from the 20s through the present:

1. Sunrise: A Song Of Two Humans

2. Duck Soup

3. Casablanca

4. The Searchers

5. Pierrot Le Fou

6. Taxi Driver

7. Do The Right Thing

8. Miller’s Crossing

9. Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon

Wish us luck. Further updates to follow if and when The End draws near.

Movie Roundup: Bergman Hates Kittens Edition

Trying not to fall behind again, here’s the last few movies I’ve watched.

300 – Going in I figured it would either be really great or really terrible, but definitely nothing in between. I was sort of right: it’s both really great and really terrible. Over the top across the board, which works great for the action scenes and the general Spartan speechifying. But there’s way too much of the Queen’s actions on the homefront, trying to rouse the Spartan Council to war despite the evil presence of Jimmy McNulty. Any attempt to look at the film as a political statement is bound to end in fascism or worse. Let’s be kind and just call it politically irresponsible. Several images though, lifted straight from Frank Miller’s graphic novel, I understand, are breathtaking. Gerard Butler, as the King Leonidas is surprisingly good in a role that basically requires him to cause mayhem, shout and look at the sun. Rodrigo Santoro is simultaneously awesome and hilarious as Xerxes. And, hey, Faramir’s there too!

Abraham Lincoln – Well, that didn’t really help. I was trying to erase thoughts of DW Griffith’s paean to the KKK by watching this, which I’d heard some good things about. It’s a fairly conventional biopic, and Griffith pretty much entirely avoids the subject of slavery entirely: the cause of the War comes down to Walter Huston repeatedly glancing skyward and in a stentorian tone announcing that “The Union must be preserved!”

Visually, it’s obviously an early sound film. The sound quality was really terrible and the camera hardly ever moves (early sound cameras were to big to float around in the ways they did in the late silent era). Griffith manages to condense Lincoln’s entire life to an hour and a half, mainly by structuring the film as a collection of short scenes connected by fades. Lincoln rarely has anything more to say on an issue than a sound bite or a short folksy anecdote. Lincoln’s most famous speeches are elided together or eliminated altogether: the “House Divided” line is inserted into the Lincoln-Douglas debates (which consist of, IIRC, 6 total lines), “Malice toward none and charity toward all” from the second inaugural is moved to some remarks before Our American Cousin starts (along with the final lines of the Gettysburg address). The War is nothing but crushing defeats, until suddenly the North wins.

It’s better than BOAN in that its not actively evil, and there are some very nice framings. But Griffith’s silent work was all movement and kineticism, both in camera and in editing. This film just kind of sits there.

Le Procès de Jeanne D’Arc – Robert Bresson’s film of the trial of Joan Of Arc is a fascinating contrast to Carl Theodor Dreyer’s The Passion Of Joan Of Arc because passion is exactly the thing that Bresson attempts to remove from all his films: the kind of actorly emoting that tells the audience how to feel that is so powerful in the close ups of Maria Falconetti’s performance in Dreyer’s film is entirely absent from Bresson’s. Bresson uses the actual transcripts of Joan’s actual trial to tell a short story (only 68 minutes) that is exactly what the title proclaims it to be and nothing else. Florence Delay (perhaps the cutest Joan yet, maybe too cute) says her lines with the total lack of emotion Bresson demanded from his non-actors, unlike the intense performances Flaconetti and Milla Jovovich (in Luc Besson’s underrated The Messenger) have given in the role. not as powerful as the other Besson’s I’ve seen, but I think that’s largely a matter of the familiarity with the subject matter and the literalness of the film. Au Hasard Balthazar and Diary Of A Country Priest and even Pickpocket are open-ended narratives that leave the question of if the story is an allegory and if so, about what, up to the viewer. In Le Procès, the mystery is in the historical events, less so the film. The #5 film of 1962.

Le Procès de Jeanne D’Arc – Robert Bresson’s film of the trial of Joan Of Arc is a fascinating contrast to Carl Theodor Dreyer’s The Passion Of Joan Of Arc because passion is exactly the thing that Bresson attempts to remove from all his films: the kind of actorly emoting that tells the audience how to feel that is so powerful in the close ups of Maria Falconetti’s performance in Dreyer’s film is entirely absent from Bresson’s. Bresson uses the actual transcripts of Joan’s actual trial to tell a short story (only 68 minutes) that is exactly what the title proclaims it to be and nothing else. Florence Delay (perhaps the cutest Joan yet, maybe too cute) says her lines with the total lack of emotion Bresson demanded from his non-actors, unlike the intense performances Flaconetti and Milla Jovovich (in Luc Besson’s underrated The Messenger) have given in the role. not as powerful as the other Besson’s I’ve seen, but I think that’s largely a matter of the familiarity with the subject matter and the literalness of the film. Au Hasard Balthazar and Diary Of A Country Priest and even Pickpocket are open-ended narratives that leave the question of if the story is an allegory and if so, about what, up to the viewer. In Le Procès, the mystery is in the historical events, less so the film. The #5 film of 1962.

The Slow Century – Rock documentary about the band Pavement that’s fairly conventional as these things go. You don’t really learn anything about the band that you couldn’t learn listening to the albums and reading their Wikipedia entry. the film is largely valuable for an extensive collection of archival footage of the band’s performances, especially their early, chaotically messy shows. The #22 film of 2002.

The Missouri Breaks – Weird Western directed by Arthur Penn (Bonnie & Clyde, The Left-Handed Gun) and starring Marlon Brando, Jack Nicholson, Randy Quaid and Harry Dean Stanton. Nicholson, Quaid and Stanton are a gang of horse thieves in Montana and Brando’s the crazy guy who gets hired to hunt them down and kill them. The film never seems to decide if it wants to be serious (Stanton, various speeches about the morality of capital punishment) or comic (Brando’s overthetop wackiness, the jaunty score) or something in-between (Nicholson and Quaid). The result is a disjointed mess of a film that never feels right. It’s more jarring than interesting. The #11 film of 1976.

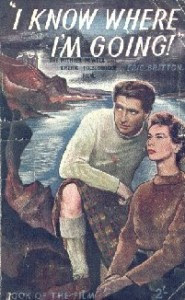

I Know Where I’m Going! – Another low-key romantic masterpiece by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger. Wendy Hiller plays a determined golddigger who gets stuck by a storm an island away from her wedding in the islands off the Western coast of Scotland. There she meets Roger Livesey, a naval officer on leave and resident of her destination island. Thanks to some traditional Scottish culture, a bit of superstition, some magic an uncooperative eagle and a very bad boat trip, they, of course, fall in love. Not as successful as the very similar A Canterbury Tale at building a romantic, quasi-mystical epiphany out f the mundane details of country life, but still a terrific film.

I Know Where I’m Going! – Another low-key romantic masterpiece by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger. Wendy Hiller plays a determined golddigger who gets stuck by a storm an island away from her wedding in the islands off the Western coast of Scotland. There she meets Roger Livesey, a naval officer on leave and resident of her destination island. Thanks to some traditional Scottish culture, a bit of superstition, some magic an uncooperative eagle and a very bad boat trip, they, of course, fall in love. Not as successful as the very similar A Canterbury Tale at building a romantic, quasi-mystical epiphany out f the mundane details of country life, but still a terrific film.

I think I’ve seen all the most important Powell and Pressburger films now. They’re all oustanding, but here’s my ranking:

1. The Red Shoes

2. Black Narcissus

3. A Matter Of Life And Death (Stairway To Heaven)

4. A Canterbury Tale

5. The Life And Death Of Colonel Blimp

6. The Thief Of Baghdad

7. The 49th Parallel

8. I Know Where I’m Going!

9. Tales Of Hoffman

Movie Roundup: Waiting For The End Edition

Since I’ve got a massive backlog, here’s a quick roundup the last 60 films I’ve watched. If you want to know more about any of them, please ask in the comments. I’ve just got to get through this list:

Since I’ve got a massive backlog, here’s a quick roundup the last 60 films I’ve watched. If you want to know more about any of them, please ask in the comments. I’ve just got to get through this list:

Curse Of The Golden Flower – Not as good as the last couple Zhang Yimou period pictures. It out-ornates even Marie Antoinette. Great performances from Gong Li and Chow Yun-fat, though Chow’s still missing his charm. Not as much action as Hero or House Of Flying Daggers, but the second most Shakespearean film of 2006, after The Departed.

Tea And Sympathy – Vincente Minelli drama about a young man who may or may not be gay and the older woman he may or may not love (played by Deborah Kerr). Brightly Technicolored complex swirl of subtexts, fascinating. The #7 film of 1956.

Rancho Notorious – Tremendously fun revenge Western directed by Fritz Lang. Marlene Dietrich stars as the proprietress of the eponymous hideout. Arthur Kennedy’s the weak link as the protagonist out to kill the men who murdered his fiance during a holdup.

The Mortal Storm – Interesting 1940 anti-Nazi film by Frank Borzage that manages to run it’s entire length without ever mentioning that the people the Nazis are killing are Jewish. Great cast including James Stewart, Margaret Sullavan, Frank Morgan and Robert Stack.

Death Takes A Holiday – The remake, Meet Joe Black is a guilty pleasure of mine. This, the original, directed by Mitchell Leisen, stars Fredric March, who isn’t half the actor Brad Pitt is. Think about that.

The Last Hurrah – 1958 John Ford film starring Spencer Tracy as an old school politician on his way out as the world changes. Basically a low-key American version of The Leopard. There’s a tracking shot towards the end that’s one of Ford’s best. The #7 film of 1958.

The Barefoot Contessa – Dreamy Joseph L. Mankiewicz film that’s the perfect Technicolor counterpart to his All About Eve. Ava Gardner plays a young dancer who gets cast in a Hollywood movie, becomes rich and famous, marries a Count and has everything fall apart. Also stars Humphrey Bogart (“What’s the Spanish word for ‘Cinderella’?”) and Edmund O’Brien.

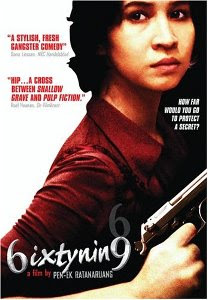

6ixtynin9 – Pen-Ek Ratanaruang’s Tarantino-esque comedy-thriller about an unemployed girl who has a fortune fall into her lap and her attempts to keep it from the hoodlums who keep killing each other in her apartment while trying to retrieve it. A lot of fun, but never as sublime as his Last Life In The Universe. The #12 film of 1999.

6ixtynin9 – Pen-Ek Ratanaruang’s Tarantino-esque comedy-thriller about an unemployed girl who has a fortune fall into her lap and her attempts to keep it from the hoodlums who keep killing each other in her apartment while trying to retrieve it. A lot of fun, but never as sublime as his Last Life In The Universe. The #12 film of 1999.

Children Of Men – Entertaining, but flawed dystopian action film by Alfonso Cuarón. In the not too distant future, the human race can’t reproduce which causes repressive anti-immigrant hysteria in England as the last bastion of civilization on Earth. Clive Owen has to escort a miraculously pregnant young woman out of the country. The art direction is clever and inventive, and the film is already famous for its impressive long tracking shots. The technical virtuosity combined with the political allegory establishes a serious mood that’s undermined by the humor of the mise-en-scène and the inherent silliness of the film’s central remise. The incongruity leaves the film neither fish nor fowl, but platypus. The #5 film of 2006.

Platform – Director Jia Zhangke’s semi-autobiographical film about a traveling musical comedy troupe in post-Cultural Revolution China. Wistful, nostalgic and more than a little confusing at times (it can be hard to keep all the characters straight on first viewing) the film’s at heart a generational coming of age story along the lines of American Graffiti or Dazed And Confused. The #5 film of 2000.

Dr. Mabuse: The Gambler – Four hour Fritz Lang silent that was the first in his trilogy of films about criminal mastermind psychologist Mabuse. It’s fun to see Lang inventing both film noir and the crime thriller in general bit by bit as he goes along, the film is archetypal. But it’s hampered by what has to be one of the dumbest detectives in film history.

13 Ghosts – Low-budget British horror film from 1960 directed by William Castle. Like seemingly all horror films, the lower the budget, the more effective it is. A very creepy haunted house movie with some mediocre acting, cheap special effects and some rather confusing, if silly, plot twists at the end. The #12 film of 1960.

Last Year At Marienbad – Alain Resnais’s masterpiece about a pair of lovers who may or may not have met one year before at the same palatial estate/luxury hotel. One of the most beautiful black and white films ever made, filled with long tracking shots through the house and its surrounding grounds. The plot, such at it is, is a puzzle that may or may not have a solution. Unlike the tick movies of the last decade, however, it’s a film that grows and deepens with every viewing. A must see for any film fan. The #3 film of 1961.

The Proposition – Bleak, Peckinpaugh-esque Australian Western written by Singer/songwriter Nick Cave. Some nice landscape photography, particularly the sunsets. Fine performances by Ray Winstone and Guy Pearce, but doesn’t really add anything new to the genre, aside from the accents. The #18 film of 2005.

Elena And Her Men – Charming Jean Renoir romantic comedy with Ingrid Bergman as a Polish princess with a variety of suitors. Effortlessly fun and enjoyable, the Technicolor costumes create a mood of vibrant buoyancy. The #5 film of 1956.

The Long Goodbye – Another in a string of Robert Altman masterpieces from the early 70s (along with MASH, McCabe & Mrs. Miller and Nashville). Elliot Gould turns Raymond Chandler’s detective Philip Marlowe on his ear in a post-hippie adaptation of the author’s hard-boiled crime novel. With pitcher Jim Bouton as Marlowe’s murdered friend and Sterling Hayden as the drunken great author who may be a suspect. The #4 film of 1973.

Portrait Of Jennie – Joseph Cotton stars as a starving artist who meets a girl (Jennifer Jones) in the park who inspires him to paint some salable pictures. He becomes rather confused as each time he meets her, she appears much older than before, but he heedlessly falls in love with her anyway. The film, directed by William Dieterle, won a special effects Oscar thanks to some cool-looking dissolves as the film frame gradually gains the texture and grain of a painting on canvas.

Goodbye South, Goodbye – Hou Hsiao-hsien’s gangster film is about as far away from the pyrotechnics of Scarface as you can get. The set up is familiar enough: veteran gangster is trying to go straight but the younger gangster he’s got to look out for keeps screwing things up for the both of them. You may remember that from such films as Mean Streets and Wong Kar-wai’s As Tears Go By. But the film’s told in Hou’s unique style: long deep focus shots with multiple planes of character and movement always keeping things interesting. Only in a Hou movie can you see a five minute-take and not realize there’s a character at the bottom of the screen until the fourth minute. The #10 film of 1996.

Goodbye South, Goodbye – Hou Hsiao-hsien’s gangster film is about as far away from the pyrotechnics of Scarface as you can get. The set up is familiar enough: veteran gangster is trying to go straight but the younger gangster he’s got to look out for keeps screwing things up for the both of them. You may remember that from such films as Mean Streets and Wong Kar-wai’s As Tears Go By. But the film’s told in Hou’s unique style: long deep focus shots with multiple planes of character and movement always keeping things interesting. Only in a Hou movie can you see a five minute-take and not realize there’s a character at the bottom of the screen until the fourth minute. The #10 film of 1996.

Hamlet – Michael Almereyda’s version, with Ethan Hawke as the melancholy Prince, Julia Stiles as Ophelia, Bill Murray as Polonius and Geoffrey Wright, Kyle McLachlan, Liev Schreiber, Steve Zahn and Sam Shepard along for the ride. The play’s recent in the world of a contemporary corperation, with Hamlet as a video artist. Self-consciously artsy, it’s the kind of adaptation people who call things “pretentious” would hate. The actors are fine, but the only thing that stands out is the vaguely silly mise-en-scène. The #11 film of 2000.

Hell In The Pacific – A can’t recommend this forgotten masterpiece highly enough. Sometime in World War 2, two soldiers are stranded on a deserted island: one American and one Japanese. The American is Lee Marvin and the Japanese is Toshiro Mifune. neither speaks the others language, and Mifune’s dialogue is not subtitled. At first the two are antagonistic: Marvin trying to steal the water Mifune’s gathered, trying to upset all the machines Mifune’s built, generally trying to kill each other. Eventually, they decide to work together to build a raft and escape. The direction, by John Boorman and the cinematography by Conrad Hall are Malickian. The #5 film of 1968.

The Women – The Desperate Housewives of 1939. Gossip and drama in the lives of rich, catty women. It’s got a great all-female cast though: Norma Shearer, Joan Fontaine, Joan Crawford, Rosalind Russell and Paulette Goddard. Ably directed by George Cukor.

Curse Of The Demon – Mediocre horror film in which Dana Andrews is called in to find out whether or not a demon has been conjured to murder people, who conjured it, and why. Director Jacques Tourneur made some great low-budget horror films in the 40s, but this is more The Leopard Man than Cat People or I Walked With A Zombie. The #13 film of 1957.

Sylvia Scarlett – Cross-dressing adventure comedy with Katherine Hepburn as the daughter of a embezzler on the lam. She disguises herself as a boy and falls in love with Cary Grant, a con artist they meet along the way. The three of them manage their escape, pull some cons start a variety show and meet an annoying artist. The film was a tremendous flop, Hepburn was labeled “box office poison” and it was years before she regained her stature. Directed by George Cukor.

Taste Of Cherry – The first Abbas Kiarostami film (and the film Iranian film) I’ve seen, and it’s mesmerizing. A middle-aged man is thinking about killing himself, so he drives around the outskirts of tehran looking for someone to come to a specific place the next morning (a hole he’s dug in the side of a hill) and help him out if he’s alive and bury him if he’s not. He first tries a soldier, who runs away in fear, then a religious student who tries to talk him out of it and finally an old taxidermist who agrees but only to help his sick child. The ending is one of the more astounding things in film history. The film is shot almost entirely from the interior of the car, alternating shots of driver and passenger. Apparently the dialogue is largely improvised, with Kiarostami playing the opposite part of whichever actor was being filmed at the time. The #5 film of 1997.

Taste Of Cherry – The first Abbas Kiarostami film (and the film Iranian film) I’ve seen, and it’s mesmerizing. A middle-aged man is thinking about killing himself, so he drives around the outskirts of tehran looking for someone to come to a specific place the next morning (a hole he’s dug in the side of a hill) and help him out if he’s alive and bury him if he’s not. He first tries a soldier, who runs away in fear, then a religious student who tries to talk him out of it and finally an old taxidermist who agrees but only to help his sick child. The ending is one of the more astounding things in film history. The film is shot almost entirely from the interior of the car, alternating shots of driver and passenger. Apparently the dialogue is largely improvised, with Kiarostami playing the opposite part of whichever actor was being filmed at the time. The #5 film of 1997.

The Criminal Code – Minor Howard Hawks film about a DA (Walter Huston) who gets a kid convicted for murder then becomes the warden of his prison. He takes a liking to the kid and makes him his valet. The kid falls in love with Huston’s daughter and witnesses a murder in prison. He’s got to choose whether or not to rat out the killer. The direction is fine and Huston’s always great, but the rest of the cast (aside from Boris Karloff) is pretty mediocre, and the film lacks the fierce energy Hawks would bring to Scarface a year later.

The Banquet – A loose Chinese adaptation of Hamlet, starring Zhang Ziyias the Queen and Daniel Wu as the upset son. Zhang isn’t Wu’s mother, which eases some of the incestual tension of the play, and makes the film more f a tragic romance between the two. All the principals and events are there from the play, in slightly altered form, but the tone of the thing is different. Whereas the play is a brilliant mixture of comedy and tragedy, the film is dark and moody to the point of hysteria. The sets and costumes are elaborate, but the direction and cinematography are rather pedestrian. The #11 film of 2006.

A Canterbury Tale – I don’t know how it is that Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger were able to do it: take the simplest stories an wring the profoundest emotional experiences out of them. During World War 2, an American soldier on leave, a British officer and a young girl find themselves in a small village outside Canterbury. There’s an odd criminal on the loose: some weirdo likes to pour tar in girls’ hair late at night. The three set out to capture the crook and along the way learn the joys of small-town life, and eventually, the wonder of life in general. No filmmakers have ever glided more elegantly from the mundane to the transcendent. The Archers were magicians.

Last Of The Mohicans – I was surprised at how closely Michael Mann’s version followed this 1936 adaptation starring Randolph Scott and directed by George B. Seitz, who went on to direct many an Andy Hardy film. It’s a terrific action film, but never approaches the poetry of Mann’s version. Some of the dialogue I’d always credited to 80s action movie tropes in Mann’s film are actually in this one (“Someday you and I are going to have a serious disagreement.”)

The Man In The Iron Mask – I’ve never yet read a Dumas adaptation I liked, and even the great James Whale couldn’t manage it in this 1939 film, though it’s easily the best of them. Louis XIV is an evil tyrant with a twin brother. The famous four musketeers maneuver things such that the evil twin is replaced by the good one. I’ve read a fair amount of Dumas (The several Musketeers books and The Count Of Monte Cristo) and they are cinematically written but have yet to be well-adapted. We need a four hour Three Musketeers directed by Quentin Tarantino or something.

Bill Of Divorcement – Well-made melodrama with John Barrymore as a patriarch returning home suddenly after 15 years in an insane asylum to find his wife has divorced him and his daughter’s about to get married. Katherine Hepburn plays the daughter, who increasingly becomes afraid that she’ll go nutso as well. George Cukor directs, but the film doesn’t quite escape from its theatrical roots.

Dragnet – Jack Webb’s film adaptation of his popular and ground-breaking police procedural TV series. Essentially just a 90 minute episode of said show, the only thing it really added was color, which I guess was a bigger deal then than it is now (especially since I’ve only ever seen the TV show in color). As an early attempt at a color noir, it fails. But then noir and the procedural genre only have a tangential relation. The #14 film of 1954.

Faust – FW Muranau’s adaptation of the timeless story has a delirious mise-en-scène and some fine campy scenery chewing from Emil Jannings as Mephisto, but the plot doesn’t entirely make sense (the end is literally a deus ex machina) and the lead actress, while pretty, is fairly poor. It’s not as great as the best Murnau films (certainly not Sunrise) but is still pretty terrific.

This Could Be The Night – Chalk my viewing of this mediocrity to my, understandable I think, infatuation with Jean Simmons. She plays a nice, college educated girl who gets a job as a secretary at a low-class night club. She’s charming to most of the regulars and staff, but Anthony Franciosa doesn’t like her, until, of course, he loves her. Directed by the great hit and miss director Robert Wise. The #14 film of 1957.

Arrowsmith – Mediocre early John Ford biopic about a doctor trying to cure bubonic plague. He neglects his unfortunate wife for his work, and so, of course, she ends up dying from plague. Stars Ronald Coleman and Helen Hayes and based on a Sinclair Lewis novel. Ford’s always great, but this isn’t exactly the top of his game.

Hangmen Also Die – Surprisingly terrific war film by Fritz Lang. The Nazi ruler of Czechoslovakia is murdered and the Nazi establishment tries to solve the crime. The assassin escapes to the home of a local professor (and his hot young daughter). Despite random arrests and murders, the whole Czech populace unites to protect the assassin. A moving and entirely effective war film with a co-story credit for Bertolt Brecht. the cast includes an unrecognizable Walter Brennan, I literally did a double take when I realized it was him.

The Life Of Oharu – Man it must have sucked to be a woman in medieval Japan. In Kenji Mizoguchi’s classic film, everything that can go wrong for poor Oharu actually does. She sleeps with Toshiro Mifune, who’s below her class and gets her family kicked out of Kyoto, she gets a decent life as the second wife of a nobleman, but so angers the first one that she gets thrown out, she marries a decent merchant out of love but he dies too young, eventually she ends up an old prostitute, mocked by monks. the film would have been more moving if it wasn’t so schematic. Oharu isn’t a woman or a character, she’s a type, a political statement. Mizoguchi would make better indictments of the fate of women.

The Life Of Oharu – Man it must have sucked to be a woman in medieval Japan. In Kenji Mizoguchi’s classic film, everything that can go wrong for poor Oharu actually does. She sleeps with Toshiro Mifune, who’s below her class and gets her family kicked out of Kyoto, she gets a decent life as the second wife of a nobleman, but so angers the first one that she gets thrown out, she marries a decent merchant out of love but he dies too young, eventually she ends up an old prostitute, mocked by monks. the film would have been more moving if it wasn’t so schematic. Oharu isn’t a woman or a character, she’s a type, a political statement. Mizoguchi would make better indictments of the fate of women.

Lord Love A Duck – A truly weird high school film with Roddy McDowell as a genius who makes it his mission to fulfill every wish the ridiculously hot Tuesday Weld (the new girl in school) happens to have. Dark and satirical, the film parodies teen movies in general, along with the beach film genre, the Disney Merlin Jones series, and anything and everything serious. I don’t know if it’s brilliant, but it’s unlike anything I’ve ever seen. The #15 film of 1966.

They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? – I’ve seen this referred to as Sidney Pollack’s best film and a great film in it’s own right, but I ain’t buying it. I liked it a lot until the ending, which seemed forced and unmotivated and depressing for the sake of seeming deep and serious. Give me Out Of Africa any day. Anyway, the story is that jane Fonda and red Buttons and Bonnie Bedelia and Bruce Dern are all in one of those endless dance marathons of the Depression. They’re poor and desperate and exploited for the entertainment of others, but that’s show business. The #6 film of 1969.

The Killer Is Loose – Joseph Cotton stars in this procedural about a cop who captures a bank robber and gets him placed behind bars. When the psychotic crook escapes, he goes after Cotton and his wife. A taut, no nonesense thriller that doesn’t resonate much beyond basic suspense. Directed by Budd Boetticher, and reportedly one of his lesser films. The #12 film of 1956.

El Dorado – I’d occasionally heard that this Howard Hawks film was superior to his film it is a remake of, Rio Bravo, but I never believed it. But, honestly, now that I’ve seen it. I think it might be. Te premise is the same: John Wayne, an old man, a drunk and a young kid have to hold off a gang of outlaws until the marshall shows up to take away a killer. This version trades Robert Mitchum for Dean Martin and James Caan for Ricky Nelson, a acting improvement in both cases. It also adds some interesting backstory and vulnerablizes the heroes. For example, Wayne, instead of the superpowered John T. Chance of the first film is a flawed man who accidentally kills someone in the first 15 minutes of the film and isn’t necessarily always on the side of the law. Both films are great, but this may very well be better. The #6 film of 1966.

On Dangerous Ground – Odd little Nicholas Ray noir with Robert Ryan as a cop so close to the borderline of police brutality that he gets sent upstate to help solve a murder in a small town. Ward Bond plays the father of the murder victim, anxious to shoot the killer, but Ryan’s heart warms when they track the killer to Ida Lupino’s house, a pretty blind girl who takes care of her disturbed brother, the murderer. Simple and moving.

The Spiral Staircase – Horror noir about a serial killer on the loose who prays on invalid young women. Directed by Robert Siodmak with some nice POV shots and a spooky mise-en-scène that elevates the rather simple story and pedestrian acting by Dorothy McGuire, George Brent and Ethel Barrymore.

Tears Of The Black Tiger – A Guy Maddin version of a Sergio Leone story, in Thailand is director Wisit Sasanatieng’s action film. A frenetic, melodramatic score, some over the top violence and lushly colored visuals amke for a highly entertaining culture and genre mashup. The #9 film of 2000.

Lost Horizon – A group of Brits are kidnapped and crash-landed in the mysterious land of Shangri-la, where they experience a paradise that literally too good to be believed. Director Frank Capra’s idealism infuses the film, but the cast led by Ronald Colman, Jane Wyatt and Edward Everett Horton isn’t quite up to the task. An odd misfire of a film, a complete version doesn’t appear to exist, there’s a long, slow-moving middle section and some 1930s nudity. And the ending doesn’t really work.

Hamlet – The 1948 version by Laurence Olivier, and I’m not a fine. It’s well-directed, with a noirish mise-en-scène that’s entirely appropriate to the material and some elegant tracking shots between scenes that establish the space of Elsinore Castle quite nicely. But I have two major problems with the film. First, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are almost entirely eliminated, along with my favorite speech from the play (“I could be bounded in a nutshell and count myself the king of infinite space were it not that I have bad dreams.”). Second, and most importantly, the acting is the worst kind of Shakespeare there is: recitation, not performance. This was a problem in Olivier’s Henry V as well, a film about passion that was totally lacking in passion. Here, Olivier manages to play a line like “Now could I drink hot blood!” as if he had a hankering for a nice cup of tea. Give me Mel Gibson and Franco Zefferelli any day.

Street Of Shame – A more realistic Mizoguchi feminist film, this time set in the present as anti-prostitution laws are being debated by the Japanese government (supposedly this film helped get those laws passed). The film centers on a single brothel and the various trials the girls that work there are put through. Not as poetic as Hou’s Flowers Of Shanghai, made 45 years later, but more effective as a political statement, not that the two are not interrelated effects. The #6 film of 1956.

Hype! – Documentary on the Seattle music scene of the 1980s and early 90s. Some interesting interviews with now unknown members of that scene, but there’s little that’s insightful to someone who grew up during the grunge explosion. There’s the familiar Northwest paradox of everyone trying to be rich and famous while disdaining all things rich and famous as sellouts or lame or whatever. Also odd that the film manages to go one for 75 minutes before it ever mentions drugs, the prime mover that corrupted and eventually destroyed the whole thing. A fine record and worth watching. The #26 film of 1996.

A Star Is Born – This, the original 1937 version of the oft-remade story directed by William Wellman I liked a lot better than the more famous remake starring Judy Garland and James Mason and directed by George Cukor. This time, Janet Gaynor (Sunrise) plays the young girl who makes it big in Hollywood as her big star husband descends into drink and obscurity. There’s no way I’d ever choose the cedarian Fredric March over James Mason, one of my favorite lesser stars, (and likewise Wellman over the great Cukor) but this film works a whole lot better with Gaynor and a lack of musical numbers. It’s a great story and hard to do wrong (though i suspect the Barbara Streisand version manages it). The two-strip Technicolor process gives a quite unusual look to the film that’s worth watching just to see.

Sisters Of Gion – My favorite of the Mizoguchi anti-prostitution film, this time he boils the story down to two “sisters” who share a house and a struggle for clients. One gets screwed over by a man she thinks loves her and the other sees her manipulative schemes fail and create misery for everyone, but most especially herself. It’s also got a fair amount of humor, something which Mizoguchi’s other films aren’t especially successful at.

Story Of The Last Chrysanthemums – I managed to see this and A Star Is Born in the same day, which was rather serendipitous, as both films are about the difficulty and costs of an acting career. This is easily my favorite of the Mizoguchi films that played here recently that I’d yet to see, and not just because there wasn’t a prostitute in sight. It’s less schematic and obviously political than the others, but just as fundamentally humanist. It’s about a young kabuki actor who sucks but no one will tell him because his father is famous and successful. He falls in love with his nephews servant, who has the nerve to tell him he isn’t very good, and the two of them run off to hone his acting kills on the road. You can imagine the course of the melodrama from there, but it’s nonetheless tremendously moving and effective.

Monsieur Verdoux – A terrific late Chaplin film about a serial killer just trying to support his family in the years before the Depression. He charms old ladies, marries them and then inherits their money after murdering them. Totally lacking in the sentimentality that colors far too many of Chaplin’s films, it also avoids the nostalgia of the otherwise great Limelight or the political aggressiveness of The Great Dictator. Chaplin’s too old for the best of his physical comedy, but the movie still manages some moments of hilarity, especially in his interactions with Martha Raye as his most obnoxious wife.

Monsieur Verdoux – A terrific late Chaplin film about a serial killer just trying to support his family in the years before the Depression. He charms old ladies, marries them and then inherits their money after murdering them. Totally lacking in the sentimentality that colors far too many of Chaplin’s films, it also avoids the nostalgia of the otherwise great Limelight or the political aggressiveness of The Great Dictator. Chaplin’s too old for the best of his physical comedy, but the movie still manages some moments of hilarity, especially in his interactions with Martha Raye as his most obnoxious wife.

Speedy – On the basis of this, my first Harold Lloyd film, I’d say there’s no way his in the class of Keaton or Chaplin as silent film comedians go. A collection of set-pieces, on a couple actually work: Lloyd as a terrible cab driver who ends up scaring the hell out of Babe Ruth, Lloyd and his girl in Coney Island in a sequence that has a lot in common with the amusement park sequence in Sunrise, except the Murnau is sublime while the Lloyd is mediocre, and the final race against the clock as Lloyd high-speed drives a horse-drawn train all the way across New York.

Cleo From 5 To 7 – Agnes Varda’s chronicle of two hours in the life of a singer who things she might have cancer. The film starts off has a lot of fun as the singer and her old friend go hat shopping and ride around town in a cab, turns a little weird as she fights with her songwriters (one of whom is played by the great film composer Michel Legrand), and picks up again as she meets a soldier in a park. It’s the only Varda film I’ve seen thus far, though I’m a huge fan of two of her husband’s movies: The Umbrellas Of Cherbourg and The Young Girls Of Rochefort, The #6 film of 1961.

Pandora’s Box – GW Pabst’s famous silent film about a sexy girl and the havoc she wreaks on a decent family. She marries the father and drives him to kill himself on their wedding night. The son falls for her and helps her to escape in a scene reminiscent of a Bob Dylan song. The daughter’s not too subtly gay and in love with the girl as well: all three of them, along with the girl’s father and a variety show producer end up in a gambling den where they not so slowly go throw away all their money. Eventually they end up destitute and victims of a serial killer. Louise brooks is radiant as the heroine, Lulu, and her haircut was the model for Anna Karina’s in many a Godard film.

The Circus – Classic Chaplin silent has the Tramp join a circus. Closer to his manic shorts than his more ambitious features like City Lights or The Gold Rush, it also manages to avoid the sentimentality that drives me crazy in those otherwise great movies. I’ll take the ending of the Circus over City Lights any day, but that’s just the kind of guy I am.

Objective: Burma! – A very fine Raoul Walsh war film with Errol Flynn as the leader of a group of American paratoopers trapped behind enemy lies after a successful attack on a radar station in World War 2. Made in the midst of the war, it’s an obvious propaganda piece, not just in the opening and closing titles, but also in the generic demonization of the Japanese enemy. A Pacific theatre version of William Wellman’s Battleground, or an inland Sands Of iwo Jima, it works to set the archetype of the WW2 movie that so many folks have been demolishing for the last 60 years.

Objective: Burma! – A very fine Raoul Walsh war film with Errol Flynn as the leader of a group of American paratoopers trapped behind enemy lies after a successful attack on a radar station in World War 2. Made in the midst of the war, it’s an obvious propaganda piece, not just in the opening and closing titles, but also in the generic demonization of the Japanese enemy. A Pacific theatre version of William Wellman’s Battleground, or an inland Sands Of iwo Jima, it works to set the archetype of the WW2 movie that so many folks have been demolishing for the last 60 years.

The Leopard – Luchino Visconti’s elegiac story of Sicily during the wars of reunification in the 1860s. Burt lancaster plays the Prince Of Salina who sees his old order collapsing in the wake of political turmoil and does what he can to ensure his family’s success in the post-Garibaldi world. Alain Delon plays his nephew, who’s marriage he arranges to the daughter of a vulgar, corrupt local politician for whom he foresees great wealth and power. He doesn’t hurt that the daughter’s played by the ridiculously beautiful Claudia Cardinale. If the scenery reminds you of The Godfather series (especially the Sicilian parts) that’s no coincidence. The #8 film of 1963.