Moonrise – The last film of director Frank Borzage’s career as a steadily working director (he doesn’t have another imdb credit for ten years) is one of his best. A swampy noir set in the deep South, in some ways it anticipates Charles Laughton’s Night of the Hunter, though it lacks that film’s wild genius. Dane Clark plays the son of a convicted and executed murderer who grows up barely enduring the taunts of the other children in his small town. Finally, in young adulthood, he fights back and accidentally kills one of his tormentors. He succeeds in hiding the body, for awhile, but his guilt begins to eat away at him and the law eventually picks up his trail. More than a vehicle for noir-plotting, the film is a close-up look at the prejudices and pleasures of small town life, a distant, dark cousin of Jacques Tourneur’s great Stars in My Crown. The #10 film of 1948.

No Greater Glory – Another excellent Borzage film, this one from the middle of his career. It follows a gang of kids who occupy a local vacant lot with militaristic games, and their war against a rival, older gang that wants to take over their lot. The hero is the smallest and weakest kid, the only one of the gang who isn’t allowed to pretend to be an officer, and we follow his increasingly self-endangering attempts to prove his courage to his friends. The allegorical reading of the film is too obvious to be interesting. Instead, it’s a warmly fascinating look at the games kids play, the ways they interpret and distort the adult world around them. The film looks at the kids not as avatars for a message of world peace (or whatever), but rather directly as fully functional human beings, ones just as capable of foolishness, bravery, treachery and redemption as any grown up. few films have ever treated children with so much respect. The #8 film of 1934.

Topper – A pleasant, relatively minor entry in the screwball comedy genre. Cary Grant (underused) and Constance Bennett (awesome) play a Nick and Nora-esque couple of rich drunks who die in a car accident and begin haunting their fuddy-duddy friend, bank executive Cosmo Topper (Roland Young, Uncle Willy in The Philadelphia Story). Grant and Bennett help Topper lighten up with their crazy ghost hijinks, and lessons are learned all around. It’s fun and mostly harmless, but it could have been better. This is a problem I have with some screwball comedies: I keep wishing they were written by Ben Hecht or Howard Hawks or Preston Sturges. This is, of course, unfair. I’d still rather watch an above average but not great romantic comedy from the 1930s than almost any romantic comedy from the 2000s. The #14 film of 1937.

The Unsuspected – This Michael Curtiz film falls somewhere between a classy mystery film and a twisted film noir. Claude Rains is a famous radio personality (he relates tales of murder!) whose secretary and niece have both died. When a man shows up claiming to be the dead niece’s husband, Rains, another niece (Audrey Totter, always welcome) and her drunk husband are suspicious. They’re more so when the supposedly dead niece returns and doesn’t remember her husband. Amnesia, a gold-digging scam, revenge? It all turns out to be a lot more obvious than the setup promises, but still, it’s a very fun film, not least because Claude Rains is always awesome. I swear, the man could have made a Dan Brown movie seem brilliant. The #13 film of 1947.

The Social Network – The best Hollywood film of the year thus far, David Fincher’s account of the founding of facebook is better than its screenplay tries to make it. Screenwriter Aaron Sorkin, as always a wizard with musical exchanges of dialogue, seems to think the film is about facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg and the Kaneian question of why he did what he did. He proposes two not necessarily mutually exclusive theories, grounded in a pair of lawsuits filed against Zuckerberg by his former associates. The first is that Zuckerberg was a social climber, jealous of his rich Harvard classmates’ fancy clubs and boat-rowing abilities (this is the lawsuit filed by the Winklevoss twins and Divya Narendra). The second is that he was brainwashed by a coke-addled Justin Timberlake into putting his own “coolness” above his relationship with his best friend (Eduardo Saverin, the source of this lawsuit). Fortunately, the film presents both theories as inadequate explanations of the facts (pretty much every idea Saverin has for the company is terrible, which should be a fireable offense, and the Winklevoss-Narendra claim on the idea is mostly groundless (the social network idea was already out there, it was Zuckerberg that made the leap that made facebook possible, etc)). Both of these possible interpretations can be taken as just that, theories proposed by individuals who are suing the person we’re trying to understand, as such, we can accept them as unreliable possibilities (the

Kane/Rashomon connection). There is a third possibility as well, which is that Zuckerberg did it all to impress girls. This appears to be Sorkin’s theory, as evidenced by the fact that it is not based in court testimony or tell-all books. Instead, Sorkin embellishes an ex-girlfriend (exaggerating the offensiveness of what Zuckerberg wrote about her in his blog), stupidly makes the facemash website sexist and ignores the fact that through this whole period, Zuckerberg had a steady girlfriend, one whom he is still seeing. In Sorkin’s version, Zuckerberg gained the whole world, but all for Rooney Mara to be his friend.

Anyway, all this plot and theme nonsense is just that, what makes the film great is everything else. Not just the performances, which are uniformly excellent, but Fincher’s direction and pacing and willingness to do crazy things like spend several minutes on a crew race in London (in contradiction to the facts, naturally) scored to a Trent Reznorized version of “In the Hall of the Mountain King” that begins with a tilt-shift establishing shot just for the hell of it (or is it that to the rich and powerful, the world is a toy? Nah, it just looks cool). Basically, I love everything about this movie except what it keeps trying to tell me it’s about, which is false and dumb and kinda sad. The movie is like ABBA: pop musical perfection trumping lyrical vapidity.

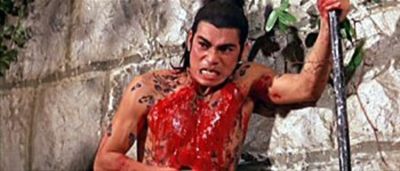

The Lineup – A taut noir procedural from director Don Siegel about heroin smugglers in San Francisco. The drugs are being put in unsuspecting travelers’ luggage, and Eli Wallach has to go around collecting the packages, killing anyone who gets in his way, before the cops catch up with him. It’s a precursor to the crime films of the late 60s and early 70s, with coolness and quiet professionalism the highest value (as in Bullitt or Le cercle rouge), as well as a fantastic bit of on-location filming (set in San Francisco, the city Siegel would return to in one of the seminal films of that later cycle, Dirty Harry). Ruthless and increasingly desperate, Wallach is as electric as always. His attempts to keep cool pay off in then end when he finally he loses it, leading to a terrific car chase, another hallmark of those later films. It might be Siegel’s best film, it’s certainly the most flawless I’ve seen. The #9 film of 1958.

5 Against the House – A weird mix of 50s college comedy, heist film and study of the psychological effects of war on young men. Brian Keith is the shell shocked one of his four vet buddies, now enrolled, thanks to the GI Bill, in a generic Midwestern University, the one prone to violent rages when some guy looks at his girl the wrong way. The brainy buddy comes up with a way to rob a casino, and the guys (plus one girl, Kim Novak) set off for Reno to pretend to pull off the crime, you know, for kicks. Then Keith goes nuts and everything gets real. It’s all pretty ridiculous, but the film deserves some credit for treating the Korean War vets with some sympathy and respect. Director Phil Karlson’s done a lot better though. Also Mike Nichols ripped off The Graduate‘s most famous shot from it. The #29 film of 1955.

Murder By Contract – Right up there with Blast of Silence, Detour and The Hitch-Hiker among the greatest truly B-level noirs ever made. Vince Edwards wants to be a hired killer, asks for the chance, waits a long time and gets the job, a job he shows remarkable skill at. That’s the first third of the film. The rest follows one job, killing a mob witness at her well-guarded Los Angeles house (the setup should be familiar to fans of Jim Jarmusch’s The Limits of Control, which might be a remake of this film). For this he’s got an audience, a pair of dumbasses along to make sure he doesn’t bungle things (not surprisingly they get in the way). Like the best low-budget films, this one takes its time. In its editing rhythms, it actually feels more like a Robert Bresson film (Pickpocket is the natural correlation) than anything being made in Hollywood at the time, though with a score inspired by The Third Man (guitar over zither, this being California). A beautiful, nasty, melancholy film, I can’t wait to see more from director Irving Lerner. The #6 film of 1958.

The Sniper – Another film that recalls Dirty Harry, which also revolves around the hunt for a serial killing sniper in San Francisco. Directed by Edward Dmytryk (and produced by none other than Stanley Kramer), the film veers dangerously close to the social problem genre, as we learn that the killer is targeting brunettes because of his mother or something. But there’s enough suspense both in the procedural aspects of the hunt and in the killer’s attempts to stop himself from killing to keep things watchable. The #21 film of 1952.

Scandal Sheet – The B-movie version of The Big Clock, with direction by Phil Karlson from a novel by Samuel Fuller. Broderick Crawford is the sleazy editor of a tabloid about to push circulation to the level that’ll make him rich when he accidentally meets his abandoned wife and kills her. He covers up the crime, but his protege and best reporter, egged on by none other than Donna Reed, are hot on his trail. It doesn’t have the investigating yourself aspect of The Big Clock and while that film is set in the rarified A picture air of rich magazine people played by big stars (Charles Laughton and Ray Milland where this film gets the volcanic Crawford, the lovely Reed and the inadequate John Derek), this film revels in its lower class world: pawnshops, broken down drunks by the dozen and the saddest dance you’ve ever seen. It’s Fuller and Karlson at their grungy best. The #15 film of 1952.