I saw my first Hong Sangsoo movie at the 2009 Vancouver Film Festival. It was Like You Know It All and it was my second favorite of the 18 movies I saw there that year. Shortly after I sought out a couple earlier Hong films (The Woman on the Beach and Woman is the Future of Man) and was underwhelmed. The familiar tropes were there (blocked director on vacation, crimes of the heart, drinking, bifurcated narrative structures reflecting in on themselves) but the moves just didn’t seem as much fun. I chalked it up to the particular circumstances of that first viewing: seeing a film at a film festival that pokes fun at the insular and more than a little absurd festival experience. Perhaps he just wasn’t as great as I thought he was.

But Hong redeemed himself in my eyes at the 2010 festival, where his Oki’s Movie and Hahaha were again two of my favorites, each film taking his formal playfulness in bold new directions while retaining the self-effacing comic spirit that initially won me over. Since then I’ve managed to see almost all of Hong’s films (including In Another Country, the most charming film of VIFF 2012 and Romance Joe, another VIFF 2012 favorite by Hong’s longtime assistant director Lee Kwangkuk). These films, along with 2008’s comparatively epic Night and Day and 2011’s Marienbad-esque The Day He Arrives amount to as remarkable an on-going streak of greatness as any director working today (Oki’s Movie remains my favorite of the dozen I’ve seen so far). Since he took 2007 off after Woman on the Beach, Hong’s made eight features in six years, counting 2013’s Our Sunhi (one of my most anticipated films of VIFF 2013) and Nobody’s Daughter Haewon, which premiered at festivals earlier this year. Hong has yet to see his festival popularity translate into proper theatrical distribution in the US. Oki’s Movie, The Day He Arrives and In Another Country all played in New York in 2012, but only the last one saw a wider release, most likely due to the art house popularity of its (French) star, Isabelle Huppert. Several of his films are available on the various streaming platforms, but he doesn’t even have his own Director’s Section at Scarecrow Video. Maybe this will be the year he finally breaks through to attain arthouse star status. My fingers remain crossed.

Continuing a recent trend, one that denotes a sharp break with his pre-2008 work, the film focuses on a female protagonist, though one who isn’t any more heroic than Hong’s usual cast of drunken, lecherous filmmaker/professors. Haewon is a pretty girl who is constantly told how pretty she is and seems to have become dependent on that flattery, no matter how poisonous it ultimately becomes to herself and the people around her. In each of the film’s sections, she conjures a man that adores her, and the film’s mysterious final line (“Waking up, I realized he was the nice old man from before”) recalls the profound final rumination from Oki’s Movie (“Things repeat themselves with differences I can’t understand”) a line that has come to epitomize so much of Hong’s work for me. One of the great pleasures of diving into the Hong universe is that each movie gains in relation to the others. No other director I know of more obsessively explores the same basic elements in film after film: a film director/student/professor who has an affair he shouldn’t have (with a friend’s wife/girlfriend, with a student, or both) while wandering cold, unglamorous Korean cities and/or vacation spots; studies of venal, hypocritical drunks that critique without judgement, the foibles of Hong’s people being ours and his rather than cruelly displayed objects for scorn, scolding and ridicule. With these basic characters and settings, and his deadpan minimalist visual style (marked most distinctively by the utterly atypical use of zooms), Hong conjures seemingly endless variations.

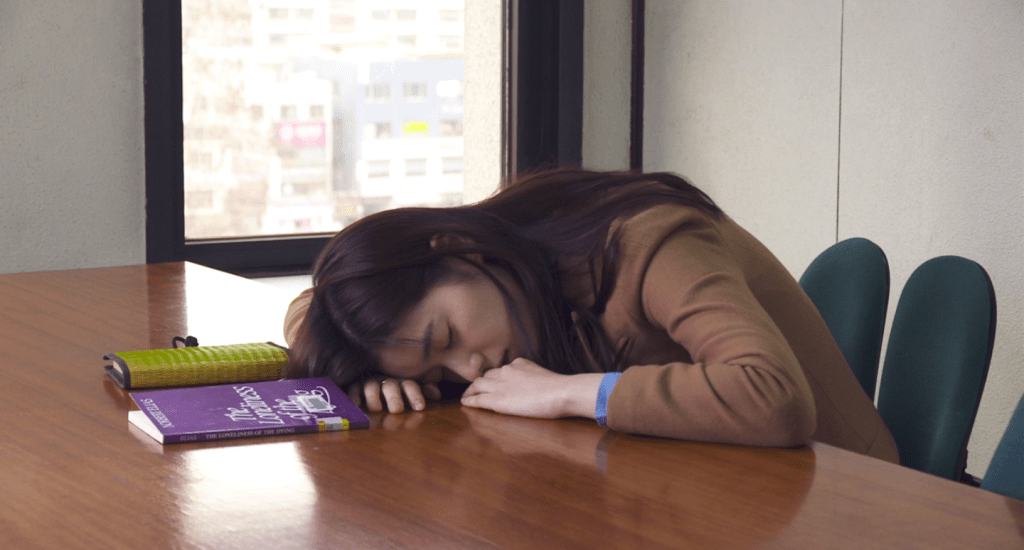

Haewon finds its closest companion in Oki’s Movie, which focuses on a student who had an affair with her professor and takes a couple of hikes up a mountain. Haewon’s affair occurred at some point in the past, though she considers rekindling it. She also takes two trips up a mountain, the location of an old fort-turned-tourist spot. Like In Another Country, Haewon features a lackadaisical to the point of abstraction framing device: three days that begin with Haewon describing them in her journal (public table, cup of coffee, handwriting in a notebook, voiceover narration) where the earlier film had the narrator writing three versions of a film she wanted to make about a French woman on vacation in Korea. On each day, the narrative is abruptly interrupted as she wakes from a dream, erasing and resetting the story as we’d known it (this also happens in the middle section of In Another Country, as well as in Night and Day). With these films, along with the four-short film structure of Oki’s Movie, the endless repetitions of The Day He Arrives, the self-delusions of Hong’s heroes have taken a metaphysical turn: not only are they not honest with themselves and each other in their romantic lives, but the very nature of their world has become unstable, liable to be rearranged or erased with the stroke of a pen or a sharp cut in the film. Where the earlier films (and also Hahaha) were built around coincidence and repetition, the later films have become Duck Amuck with horny, drunken film school denizens.

I find myself pondering the title as much as anything else. Hong usually favors straightforward titles, ones whose meaning is immediately apparent (at least lately, his early titles are beguiling in their lingering prose: The Day a Pig Fell Into the Well, On the Occasion of Remembering the Turning Gate, Woman is the Future of Man, Virgin Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors). The first section explains quite clearly that Haewon is somebody’s daughter, as it involves her spending a day with her mother on the eve of the latter’s move to Canada (Vancouver, I assume, for the film festival). The film itself begins with Haewon meeting Jane Birkin (unnamed in the film) and telling her how much she admires her daughter (actress Charlotte Gainsbourg, also unnamed). The title then has, at least, two possible meanings: given the relative fame of Birkin, Haewon’s mother is a “nobody” and perhaps this is what is keeping Haewon from becoming the successful actress she wants to be (she says she’d give her soul to have Gainsbourg’s career). Or, being sad and abandoned by her mother’s move, Haewon is forced to become an adult: she is no longer simply somebody’s daughter and must take care of herself, become an individual in her own right. She then spends the next two thirds of the film pursuing relationships with a couple of older men (both professors and therefore father-type figures) while brushing off men her own age in some kind of Freudian irony. Parent-child relationships have largely been absent in Hong’s work thus far (most of the kids have been little and mostly off-screen, as the director’s child is in Haewon). Though a mother-daughter conversation does open In Another Country. Perhaps these are the first-steps in the integration of another trope into the Hong universe, another fraught relationship with which to play and poke and have fun.

My theory is that each of the subsequent films are movies Jingu later made inspired by the situation the questioner presented: a student having an affair with her professor while she was also dating another student. In each film, he casts himself as the boyfriend/hero and Song as the morally dubious professor. In the second film (“King of Kisses”) Jingu plays the typical Hongian hero: romantic, obsessive and often drunk. This film is the most similar to the first one in both story and style (even the locations are the same: Jingu’s home in the first film plays Oki’s home in the second). One example of the rhymes between them: in each film Jingu hangs out on a park bench and falls asleep. In the second one, he meets Oki and asks her out, while in the first, he has a flashback to when he met his wife, who he suspects might now be cheating on him. (Although: maybe this is not a flashback:

My theory is that each of the subsequent films are movies Jingu later made inspired by the situation the questioner presented: a student having an affair with her professor while she was also dating another student. In each film, he casts himself as the boyfriend/hero and Song as the morally dubious professor. In the second film (“King of Kisses”) Jingu plays the typical Hongian hero: romantic, obsessive and often drunk. This film is the most similar to the first one in both story and style (even the locations are the same: Jingu’s home in the first film plays Oki’s home in the second). One example of the rhymes between them: in each film Jingu hangs out on a park bench and falls asleep. In the second one, he meets Oki and asks her out, while in the first, he has a flashback to when he met his wife, who he suspects might now be cheating on him. (Although: maybe this is not a flashback:  The third and shortest film (“After the Snowstorm”) is about Professor Song. After a blizzard, only Jingu and Oki show up for his class. The three engage in a Godardian Q & A session wherein the kids ask him about life and art he responds with gnomic aphorisms. It’s a kind of idealized version of the teaching experience, with two eager students lapping up Song’s wisdom (his best answer is when Oki asks why he loves his wife, he says “In life. . . of all the important things I do, there’s none I know the reason for. I don’t think there is.”). Later that night, after throwing up some bad octopus, Song decides to give up teaching and go back to filmmaking (“I was a bad teacher,” he cheerfully exclaims in voiceover). It’s unclear if this film takes place before during or after the love triangle situation, or if one ever even occurred in its world.

The third and shortest film (“After the Snowstorm”) is about Professor Song. After a blizzard, only Jingu and Oki show up for his class. The three engage in a Godardian Q & A session wherein the kids ask him about life and art he responds with gnomic aphorisms. It’s a kind of idealized version of the teaching experience, with two eager students lapping up Song’s wisdom (his best answer is when Oki asks why he loves his wife, he says “In life. . . of all the important things I do, there’s none I know the reason for. I don’t think there is.”). Later that night, after throwing up some bad octopus, Song decides to give up teaching and go back to filmmaking (“I was a bad teacher,” he cheerfully exclaims in voiceover). It’s unclear if this film takes place before during or after the love triangle situation, or if one ever even occurred in its world. Thus, Hong has made a film about a director who made a series of films adopting the perspectives of each of three people involved in a love triangle, based on a love triangle the director himself was once involved in. And in the end, Hong, through his character the director, through his character Oki, calls into question exactly how helpful filmmaking is as an attempt to resolve personal issues. The motive, then, for making movies has to be about something more than personal revelation. Art has to go beyond mere autobiography. The conclusion is the opposite of Alvy Singer’s in Annie Hall, where he gives the story of his relationship with Annie the happy ending it didn’t have in “reality” because “you’re always trying to get things to come out perfect in art because it’s real difficult in life.” For Alvy, the happy ending reassures him, brings him some kind of closure and perspective on his relationship. Closure that eludes Oki and the first Jingu. As for Hong himself, the answer appears to be a rejoinder to critics who presume his films, about movie directors who drink a lot and have complicated and clumsy romantic lives, are autobiographical. Movies aren’t real, they can’t be.1

Thus, Hong has made a film about a director who made a series of films adopting the perspectives of each of three people involved in a love triangle, based on a love triangle the director himself was once involved in. And in the end, Hong, through his character the director, through his character Oki, calls into question exactly how helpful filmmaking is as an attempt to resolve personal issues. The motive, then, for making movies has to be about something more than personal revelation. Art has to go beyond mere autobiography. The conclusion is the opposite of Alvy Singer’s in Annie Hall, where he gives the story of his relationship with Annie the happy ending it didn’t have in “reality” because “you’re always trying to get things to come out perfect in art because it’s real difficult in life.” For Alvy, the happy ending reassures him, brings him some kind of closure and perspective on his relationship. Closure that eludes Oki and the first Jingu. As for Hong himself, the answer appears to be a rejoinder to critics who presume his films, about movie directors who drink a lot and have complicated and clumsy romantic lives, are autobiographical. Movies aren’t real, they can’t be.1 This leads us back to the first film. Jingu the filmmaker/professor is meeting with one of his students, giving her advice on how to improve her film. “If you don’t fix it, the narrative won’t support itself. Your sincerity needs its own form. The form will take you to the truth. Telling it as it is won’t get you there. That’s a big mistake.” She accuses him of trying to impose a formal structure on her film out of greed, to make her personal statement more palatable to a mass audience. He gets angry, the form (“two turning points!”) is how the filmmaker can “take away what’s fake” in her. It’s not by being true to life that the filmmaker expresses the truth, but in submitting truth to formal constraints truth can be uncovered. Oki will realize that she made a mistake in trying to tell it like it was.

This leads us back to the first film. Jingu the filmmaker/professor is meeting with one of his students, giving her advice on how to improve her film. “If you don’t fix it, the narrative won’t support itself. Your sincerity needs its own form. The form will take you to the truth. Telling it as it is won’t get you there. That’s a big mistake.” She accuses him of trying to impose a formal structure on her film out of greed, to make her personal statement more palatable to a mass audience. He gets angry, the form (“two turning points!”) is how the filmmaker can “take away what’s fake” in her. It’s not by being true to life that the filmmaker expresses the truth, but in submitting truth to formal constraints truth can be uncovered. Oki will realize that she made a mistake in trying to tell it like it was.

![In Another Country.mkv_snapshot_00.07.53_[2012.12.10_00.45.00]](https://theendofcinema.net/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/in-another-country-mkv_snapshot_00-07-53_2012-12-10_00-45-00.jpg?w=662)