Well, we’re back home after our best film festival experience yet. 23 features in nine days is also a new record, as was the fact that there was only one day when the wife questioned why she agrees to go to these things with me. I’m sure this is going to change several times as I get some distance from the craziness of the festival environment and all these movies to settle in a separate themselves in my brain, but here’s an initial ranking of what we saw, including four of the best and most distinctive shorts.

1. Certified Copy (Abbas Kiarostami, 2010)

2. Oki’s Movie (Hong Sangsoo, 2010)

3. Uncle Boonmee Who Can recall His Past Lives (Apichatpong Weerasethakul, 2010)

4. Carlos (Olivier Assayas, 2010)

5. 607 (Liu Jianyin, 2010)

6. I Wish I Knew (Jia Zhangke, 2010)

7. Thomas Mao (Zhu Wen, 2010)

8. Hahaha (Hong Sangsoo, 2010)

9. The Sleeping Beauty (Catherine Breillat, 2010)

10. Get Out of the Car (Thom Anderson, 2010)

11. The Drunkard (Freddie Wong, 2010)

12. Poetry (Lee Changdong, 2010)

13. Gallants (Clement Cheng & Derek Kwok, 2010)

14. Strange Powers: Stephin Merritt & The Magnetic Fields (Kerthy Fix & Gail O’Hara, 2010)

15. Around a Small Mountain (Jacques Rivette, 2009)

16. The Strange Case of Angélica (Manoel de Oliveira, 2010)

17. Merry-Go-Round (Clement Cheng & Yan Yan Mak, 2010)

18. Crossing the Mountain (Yang Rui, 2010)

19. My Film and My Story (Kim Taeho et al, 2010)

20. Made in Dagenham (Nigel Cole, 2010)

21. The Fourth Portrait (Chung Mong-hong, 2010)

22. Inhalation (Edmund Yeo, 2010)

23. Of Love and Other Demons (Hilda Hidalgo, 2009)

24. The Indian Boundary Line (Thomas Comerford, 2010)

25. The Tiger Factory (Woo Ming Jin, 2010)

26. Icarus Under the Sun (Abe Saori & Takahashi Nazuki, 2010)

27. Rumination (Xu Ruotao, 2010)

And here’s index of my posts:

Day One: Made in Dagenham and My Film and My Story

Day Two: Of Love and Other Demons, Get Out of the Car & The Indian Boundary Line, Poetry and Icarus Under the Sun

Day Three: The Drunkard, Thomas Mao and Crossing the Mountain

Day Four: 607, Hahaha, The Fourth Portrait, I Wish I Knew

Day Five: The Sleeping Beauty, Rumination, Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives

Day Six: Around A Small Mountain and Oki’s Movie

Day Seven: The Strange Case of Angélica, The Tiger Factory & Inhalation and Gallants

Day Eight: Carlos and Certified Copy

Day Nine: Strange Powers: Stephin Merritt and The Magnetic Fields and Merry-Go-Round

For more on VIFF, I can’t recommend highly enough the website of David Bordwell and Kristin Thompson. Today’s dispatch from them points out that Rumination, which I saw a few days ago and didn’t particularly like, actually runs in reverse chronological order, something that went complete over my head. I don’t know if I like the movie better knowing that, but it certainly makes it more interesting.

VIFF ’10: Day Nine

Strange Powers: Stephin Merritt and The Magnetic Fields – A conventional but nonetheless engrossing documentary about, well, Stephin Merritt and his band, The Magnetic Fields. Merritt’s notoriously difficult to interview, so the intimacy of this film is rather impressive. Every major member of the band is interviewed, as well as Merritt’s mom herself. It’s mostly a biographical portrait, charting his life from high school until the Distortion album, hitting the high points (the near universal acclaim for 69 Love Songs, for my money one of the greatest works of art of the 20th Century) and the low (the racism accusations by New Yorker critic Sasha Frere-Jones, which proved nothing but the already established fact that Sasha Frere-Jones is a fucking moron. Though he was decent enough to basically admit as much both in print and on camera here). Most of the film though is funny anecdotes about Merritt’s working life, with a special focus on his 25+ year friendship with Claudia Gonson, manager and band member. Particularly cool is Merritt dumping a pile of his old notebooks on the floor and flipping nostalgically through them. (Edited to add: The coolest thing was Merritt talking about his favorite artists, particularly ABBA, who he says created such perfectly worked out songs such that when you first hear them you feel like they’ve always existed, which is exactly what I’ve always thought about Merritt’s best songs, particularly much of the 69 Love Songs). Documentaries like this aren’t generally notable for their filmic qualities, and this one is no exception. But it gets about as close as one can get to an artist like Merritt, and that’s accomplishment enough. Plus the score is really great.

Merry-Go-Round – The second film co-directed by Clement Cheng at this year’s festival (Hong Sangsoo is the only other person with two features at the festival, though as Cheng pointed out during the Q & A, his two halves make one festival film). It’s totally different in visual style from the kung fu comedy Gallants, though it is thematically quite similar. Both film’s approach Hong Kong’s past with reverence, and are about the younger generation learning to respect the older. In this case, its a young woman (the gorgeous Ella Koon), dying of leukemia who goes to HK to find an internet friend who’s been ignoring her. This friend is the nephew of another woman from San Francisco who has recently returned to HK to prevent his sale of the family’s Chinese medicine shop to developers. This older woman is obsessed with her own past: she’s also bringing her grandfather’s body back home to be buried in his home town, and she has a series of flashbacks to a romance she had before leaving for America sometime after the Communist takeover of the mainland. The desire to return a body to one’s home is one of the key motifs in the film, and much of it takes place at a “Coffin Home” where bodies of diasporic Chinese are stored until their families come to claim them. The caretaker of the Coffin Home is played by Teddy Robin (who was so great in Gallants) and he hires the dying girl and he’s got issues with the past of his own to deal with. The setup of the film is needlessly complicated, and the first half hour or so is much more disorienting than it needs to be. But once everyone settles into their places in the narrative and their various histories and interconnections begin to be revealed, the film has a powerful emotional momentum. It’s about the joy and tragedy of leaving and returning. Other than the clunky beginning and an over-reliance on the indie rock score in the latter sections of the film (the use of the standard “After You’ve Gone”, however, is excellent), it really is very good. The cinematography by first-time feature DP Jason Kwan is particularly good, much smoother and more polished than Gallants, though the budget can’t have been much greater.

VIFF ’10: Day Eight

Carlos – One of the most exciting and daunting films of the year is Olivier Assayas’s five-plus hour epic about the life of 1970s terrorist Carlos. The film begins in 1973 when Carlos, a young Marxist with nominal experience (he did spend some time in the USSR but was expelled, later he attended a terrorist training camp) adopts his nom de guerre and becomes the director for English operations for the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (which I’m pretty sure is a Life of Brian reference). The film then follows his career of largely bungled operations, many women and charts in detail the whole underground of international politics for over 20 years, until the end of the Cold War radically realigned everything and left the true believers nowhere to hide. Oscar Ramirez is fantastic in the lead role, though I kept trying to figure out who he looked like, settling on a hybrid of Val Kilmer and Johnny Depp. He brings the necessary multi-lingual charm (easily topping the excellent work of Christoph Waltz in last year’s Inglourious Basterds, if only by the fact that he spends the entire film easily switiching between English, French, Spanish and German whereas Waltz only needed a few lines of Italian) and constant threat of physical violence that must have been what enabled Carlos to last for so long in such a deadly racket and Assayas uses the actor’s body to chart the ups and downs of his career in an unusually explicit way (ie, he’s naked almost as much as the women in the film are, and sometimes he’s fat). The obvious point of comparison with Carlos will be Steven Soderbergh’s Che, another massive film about a famous 20th Century revolutionary. But I can’t think of a way in which Assayas doesn’t better that film. Whereas Soderbergh seemed to be either indifferent to Che’s politics or simply didn’t understand it, Assayas goes out of his way to contextualize Carlos and his compatriots’ ideology and that of the people they are fighting with and against, to the point that he is actually giving us the story of the decline of radical leftism worldwide in the wake of its 1968 high point (and how that relates to ongoing issues in the Middle East where Carlos’s ilk we replaced by a different, and much scarier, form of terrorist) as much as he is telling the story of one man. Soderbergh’s film shies away from anything that might make the hero look less than noble, while Assayas gives us all the warts on what was essentially a hired thug and murderer, he even makes the point that Carlos wasn’t even a particularly good terrorist: he bungled his biggest job (which takes up the heart of the film, his raid on an OPEC summit in 1975 that is a perfect hour and a half suspense film in its own right), got fired from the PFLP and never managed another major task again, even his more minor hired hits usually failed to kill the main target. Soderbergh’s film is self-consciouly arty, with changes of film stock, intercuts stories, a radically different visual style in Part Two from Part One (complete with an aspect ratio change). Assayas keeps the style unobtrusive and fluid, with generally long takes, constant spatial orientation and judicious uses of hand-held cameras. Anyway, it’s a massive and great film, he kind of intelligent action epic that simply doesn’t get made anymore (outside of John Woo’s very good, but not this good Red Cliff, I can’t think of any over the last several years) and it plays great theatrically: the five hours really flies by. It’ll play on TV in the US, but I’d see it in a theatre if you could.

Certified Copy – Maybe I’ve been watching Abbas Kiarostami all wrong, because nothing in Taste of Cherry, The Wind Will Carry Us or Close-Up prepared me for how simply funny this film is. Or maybe those films are exceptions in the career of a world class romantic comedy filmmaker. Anyway, Juliette Binoche (who somehow looks better now than she did 20 years ago, which just isn’t fair) plays a woman who invites a writer out for the afternoon as she liked his book (though parts annoyed her) and presumably because she likes him (William Schimell, he looks almost but not exactly like David Strathairn). His book is about how copies of art objects are just as valuable as the originals, because what gives art value is our relationship to it, what we see in it, and not anything inherit in the object itself. They argue about that for awhile, and eventually start to pretend to be married when they meet other people (the film’s set in Tuscany, and Binoche acts in three languages (French, Italian and English) while Schimel speaks French and English). The arguments they have as a “married” couple achieve enough reality that the audience is invited to wonder if they really are married after all, and their earlier scenes of not knowing each other the pretense. Of course, if we accept the premise of the book, it doesn’t matter: the only thing that’s important is what we as the audience take from it, how we relate it to our own lives. For me, it was funny for most of the time, as the various arguments and rhetorical strategies were not entirely unfamiliar. But that comedy is leavened by more than a little heartbreak. It’s a weird romance, but a pretty much perfect one. If I wanted to be really succinct, I’d say it’s Before Sunset for grownups. But, really it’s even better than that.

VIFF ’10: Day Seven

The Strange Case of Angelica – Eccentricities of a Blond-Hair Girl was one of my favorites at last year’s festival, and while this year’s Manoel de Oliveira film isn’t as gemlike as that one, it’s still pretty good. A young man who dabbles in photography is called upon to take the picture of the recently deceased Angelica, who has the unfortunate habit of smiling at him when she’s supposed to be dead. Both her corpse and later her image appear to move, and when she takes a ghostlike form (taking Isaac on a flight more than a little reminiscent of Superman and Lois Lane), Isaac falls in crazy obsessive love with her. In the middle of the film, there’s what appears to be an attempt to explain all of this with quantum physics and antimatter, but it doesn’t make a whole lot of sense. But then again, neither do the religious explanations (Isaac keeps repeating some lines about angels before and after meeting Angelica). While Eccentricities was a perfect little anecdote about love gone wrong, this is a much more mysterious, weird and even goofy film. The best part about it is also one of the best things about Eccentricities: both films seem to exist in technology, environment and social habits in a world that isn’t quite the present, nor is it the past. They’re not so much outside of time, but take place across the span of the whole of the 20th Century at once.

The Tiger Factory – We saw director Woo Ming Jin’s Woman on Fire Looks for Water earlier this year at the San Francisco International Film Festival, and I thought it was promising, a quirky minimalist film with some nice camerawork and a good sense of place. So I was looking forward to this, Woo’s next film. I wasn’t prepared, however, for it to be so totally unlike that other film, with a deadly serious verite-realist style instead of long takes and quasi-mystical goofiness. About all they have in common is the Malaysian setting and long sequences of people at work (catching, sorting and cleaning fish and shellfish in the first, inseminating pigs in this one). Lai Fooi Mun plays Ping, who wants to quit her three jobs (pig farm, restaurant and surrogate mom for her aunt’s baby factory) and get herself smuggling into Japan, apparently so she can advance to the world of foreign prostitution. Her aunt keeps her poor and pregnant, steals her kid and her money and is pretty much the most evil person ever. Ping has a friend and roommate at the beginning of the film, but by the end the friend has made it to Japan and is, for some reason, no longer returning Ping’s phone calls. The girl’s life sucks and there’s no possible way out of it. This would be more moving if Ping had any kind of personality or spark. But by the time the film has begun, her horrible life has already beaten her done to the point of near-mute passivity (when her various money-making plans go awry, she mopes and comes up with even dumber schemes). Basically, it’s like Chop Shop without the charm, energy or hope. The film was paired with a short called Inhalation featuring some of the same actors in a slight variation on the same story by Edmund Yeo, the co-writer and producer of The Tiger Factory. I liked the short a lot better, both for its style (there’s a cool long pan that doubles as a 38 day time jump) and its tone (Ping has a friend, and they talk like real people!). It’d go better at the end of the feature than the beginning (the way it was programmed).

Gallants – A comical kung fu film from the directing team of Clement Cheng and Derek Kwok that unites some elderly Shaw Brothers stars in a funny and moving elegy to old age and the martial arts classics of the 1970s. Skinny and clumsy real estate agent Cheung is sent to a small town to facilitate the sale of a local teahouse that happens also to be a former kung fu gym. The two owners (Dragon and Tiger) are the last surviving disciples of their coma-striken master. Bad guys (who want to buy the teahouse at a deflated price) attack, the master wakes up and everyone learns kung fu for the big local tournament. Dragon is played by Chen Kuan-tai (Crippled Avengers, Executioners from Shaolin) and Tiger by Leung Siu-lung (Legend of the Condor Heroes, Kung Fu Hustle) and both are still outstanding in the action sequences, if not the greatest actors in the world. Teddy Robin, a Hong Kong rock star in the 60s, plays their master as a mix of Yoda and Tracy Morgan, he’s by far the best part of the film (and even did the music as well). The film isn’t nearly as polished as the later Stephen Chow films, though it’s often just as funny and shares the same anarchic spirit. The quickie vibe (if I remember the Q & A correctly, they shot the whole thing in only 18 days, which is ridiculous) only makes it more fun.

VIFF ’10: Day Six

VIFF ’10: Day Five

VIFF 2010: Day Four

607 – Before getting to Day Four’s films, I wanted to mention this short by Liu Jiayin that played before Day Three’s showing of Thomas Mao. Liu made my favorite film from last year’s festival, Oxhide II, which also happens to be the highest rated film directed by a woman on my recent Top 600 Films of All-Time list. This 17 minute short consists mostly of one shot of a bathtub in a hotel room (the hotel apparently commissioned the film). A plastic fish, manipulated by Liu’s father, with only his hands visible, swims in the water and encounters some mushrooms, a cloudy sky and a fish hook. The mushrooms are played by Liu’s mother and Liu herself is the sky and hook. It’s a marvelous bit of silliness that conveys all the warmth of a family at play.

Hahaha – The first of two films directed by Hong Sangsoo at this year’s festival, it begins, unsurprisingly for Hong, with two old friends drinking and telling stories about women. The film proper is comprised of these two stories, which end up being about the same woman, though neither knows it, while the frame is played in black and white stills with voiceover (and lots of “Cheers!” as the two drink quite a lot). The Hong films I’ve seen all have a split structure, with the second half of the film telling a new story with some of the same characters in a way that mirrors and comments upon the events of the first story. This film has that same structure, but the stories are intercut instead of segregated. This makes the film a lot easier to watch, and this is definitely the film I’d recommend to anyone who hasn’t seen a Hong Sangsoo film yet. As for the stories themselves, they’re Hong’s traditional terrain of romantic misadventures and misunderstandings and lots and lots of drinking. Again there’s a character who’s a film director, this time he falls for a tour guide who’s dating a poet who is best friends with a guy who’s on vacation from his wife with his girlfriend. It’s this last guy and the director who are the two narrators of the film. It’s as funny as Like You Know It All, one of my favorites at last year’s festival, if not quite as weird and certainly not as insidery about film festival life.

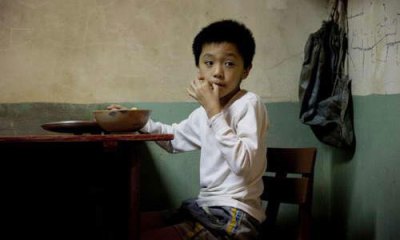

The Fourth Portrait – This Taiwanese film is about a precocious young boy named Xiang whose father dies, sending him first into the helpful hands of the school janitor, and then back to his mom, a prostitute (naturally) and step-father (who’s pretty much pure evil). Director Chung Mong-hong keeps this dire material much lighter than one would expect. Though the kid’s situation is rough and potentially terrifying, there’s enough humor and visual style (there are traces of both the Taiwanese New Wave and Wong Kar-wai, the latter especially in the scenes at the mom’s “lounge”) that things never get as horribly depressing as they might in a lesser film. There’s even a musical bit that sounds like a Chinese version of the Carl Orff song used in Badlands and True Romance). Xiang is surrounded by helpful adults, from the elderly janitor to a small time hustler to a concerned teacher. Even his mom is a decent sort. We never get the sense that Xiang’s situation is hopeless, instead, we can be sure that he’ll survive and thrive. The title comes from a series of drawings Xiang makes throughout the film: the first is his father, the second his friend the hustler, the third his older brother who may be haunting him and the fourth, more than a little cheesily, is the film itself.

I Wish I Knew – After last year’s excellent 24 City, I wasn’t quite prepared for this latest film from Jia Zhangke. While that film was a documentary that mixed scripted and acted interviews with real-life talking heads in a way that made one question the nature of documentary realism, this film is pretty much a straight and conventional film. It’s an epic collection of stories about Shanghai, told by the people who lived there and the children of the people who lived there. Shanghai was the epicenter for the most important developments in China over the 20th Century, from the European occupations to the Japanese invasion to the Civil War between the Communists and Chaing Kai-Shek’s KMT to the Cultural Revolution to the embrace of capitalism in the late 1980s. Even the Chinese film industry was based there for much of the century. Jia’s 18 interviews tell these stories in detail, with communists and KMT generals and movie stars and directors. Wei Wei appears, which marks two days in a row that we saw a film featuring this 88 year old actress, after The Drunkard. Also interviewed are Hou Hsiao-hsein (who’s actually the only person who doesn’t share a personal anecdote, he just talks about his film Flowers of Shanghai, though like many people in the film, his parents came to Taiwan from Shanghai ahead of the Communist victory). The film is very loosely structured, with the interviews coming not in chronological order of their stories, but rather the geographical order of where they have spread out. The Shanghai diaspora mainly went to Taiwan and Hong Kong, and so Jia goes to each of those places to seek out their stories. But these interviews are interspersed with scenes of present-day Shanghai, where frequent Jia star Zhao Tao wanders mutely around the sites of the old stories, neatly tying the old and new, the diasporic and the homeland together. It’s a beautiful film, about as good as a straight documentary can be.

Short Celebrity Addendum: Jia was there last night for a Q & A (he’s serving on the jury at the festival this year for the award for new Asian filmmakers that they’ve given out for 17 years or so, having previously won the award for his own first film Xiao Wu). I don’t know that I’ve ever been so giddy in a movie theatre. And then this morning, waiting in line for Catherine Breillat’s Sleeping Beauty, I’m pretty sure we were standing behind a very confused Wallace Shawn (the screening was delayed for projection reasons and the staff were giving confusing directions to the old people). I attempted to help the maybe-Shawn through the line, but he either couldn’t hear me or was too confused to pay attention to a much taller man.

VIFF ’10: Day Three

The Drunkard – Freddie Wong’s debut film is an adaptation of one of the most famous modern Chinese novels, written by Liu Yichang. In early 60s Hong Kong, a struggling writer juggles his declining career prospects (he goes from Hemingway ambitions through martial arts novels and screenplays to pornography), various women (a landlord’s 17 year old daughter, a couple of prostitutes, old and young, an elderly landlady played by Wei Wei, the star of the 1948 classic Spring in a Small Town) and copious amounts of alcohol. Wong Kar-wai’s In the Mood for Love and 2046 are somewhat based on similar characters, though his films are so infused with his own obsessions that it’d be a stretch to call them adaptations. That the film was made for a mere $500,000 is remarkable, though it does explain the intimacy of the cinematography: almost always medium to close shots of small interiors. The nightclub scenes have the Christmas tree red glow you’d expect, but there’s nothing glamorous about the writer’s alcoholism. Neither is it ever reduced to any kind of social problem picture preachiness: he drinks and he writes, but not necessarily in that order. John Chang (the father of Chang Chen, star of Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon) is terrific in the lead role, nowhere near as debonair as Tony Leung in the Wong films, he brings a weary reality to every scene.

Crossing the Mountain – Vancouver may not have gotten Jean-Luc Godard’s Film Socialisme, but we’re not wholly bereft of intentionally partially-subtitled avant-grade narrative films. Yang Rui’s opaque film, photographed in sharply focused, long-take HD, is set in Yunnan, along the Burmese border, the people here speak a local language, and she has chosen to only subtitle the “important” parts of the dialogue, even for the Chinese-speaking audience. Mostly a set of discrete, seemingly plotless episodes that are nonetheless pregnant with possibly meaningful images and juxtapositions, with more or less the same set of characters for most of the film who inexplicably disappear in the later sections (though we may have some clues at to their fate). It might be about the dangers of unexploded ordinance in Southeast Asia (still a problem, even in areas where the wars have been over for 30 years), but more than that it’s about living in a collision between past and present. The film is set in land that once belonged to a people that until quite recently practiced human sacrifice as agricultural aid (where these people are now, we can’t say, but assume they have merged with the general population), where kids try to watch TV and play karaoke video games (though the technology never seems to work properly) and old people pass the time with folk dances that look not unlike the Hokey-Pokey. Basically, it’s an impossible film to describe, and apparently quite difficult to sit through. Despite a warning from programmer Shelly Kraicer about the film’s difficulty and the need for patience with it, about the third of the audience walked out. I was glad to stay through the end. While it wasn’t the best thing I’ve seen at the festival thus far, I certainly haven’t seen anything quite like it.

VIFF ’10: Day Two

Of Love and Other Demons – An adaptation of a Gabriel García Márquez story that I haven’t read, Hilda Hidalgo’s first film is about a teenaged girl in 19th Century Cartagena, the daughter of a Marquis, who gets bit by a rabid dog. Despite the Marquis’ disbelief, he is unable to prevent the local Catholic authorities from imprisoning her under suspicion of demonic possession (apparently the Devil works through rabies). The priest assigned to examine her of course falls in love with her (she’s not a stunning beauty, but has a fabulous head of red hair, three feet long and shockingly clean for the 18th century) to the detriment of his ecclesiastical career. More straightforward than I would expect from García Márquez, the film is essentially an ecofeminist parable about the evils of patriarchy, imperialism and the Church and its destructive effects on the environment (the girl is frequently seen communing with insects, and one of the reasons she’s suspected of being possessed is that she can speak the African languages of her family’s servants). It does leave open the much more interesting possibility that the girl actually is possessed, with the devil using her to wreak havoc with the nobility and Catholic hierarchy in the later stages of the Spanish Empire.

Icarus Under the Sun – A very low-budget film made by two Japanese women (one wrote and directed and stars, the other shot, directed and plays a supporting role) that’s a grungy, realist account of a young woman trying to find her way in Tokyo. She gets a job at a mahjong parlor and befriends the eccentrics who work and hang out there: the blind ex-thief owner, the slightly crippled boy named after Alain Delon, the crazy woman who loves the blind owner, etc. Of all the young adult coming of age films we’ve seen at the several festivals we’ve been to, this is bar far the most serious and probably also the most DIY. The dreariness of the girl’s life (always in darkness, the various characters dislike of sunshine is a key motif) is almost oppressive. In the end, she manages to escape into the daytime, but I don’t know that the catharsis is enough to compensate for the misery of the first 75 minutes of the film. I needed some air.

VIFF ’10: Day One

We’re back at the Vancouver Film festival for the third year in a year and unlike the 08 and 09 festivals I’m going to not only try and write about the films we see before six months have passed, but day by day as we watch them. We’ll see how it goes. Anyway, we arrived in town this afternoon and made it to two films tonight.

Made in Dagenham – Sally Hawkins is already getting some Oscar buzz for her performance in this crowd-pleasing dramatization of a strike at a Ford plant in the UK in 1968. The workers are the 187 women (out of 55,000 in the country) who sew the interiors of the cars together, and are classed as unskilled labor and make far less than comparable male workers. The strike quickly becomes about equal pay for equal work, annoying every man in the country (except Bob Hoskins, ho helps the striking women out). Hawkins is excellent as the leader of the strike, she manages to be both shy and fiery at the same time (and she deserved the Oscar a couple years ago for Happy-Go-Lucky, so even if this performance isn’t as singular as that one, I wouldn’t begrudge her any hardware she gets for it). Miranda Richardson does a lot of funny yelling as the government minister who follows the strike from a distance, and Richard Schiff (from The West Wing) is appropriately menacing as Ford’s American representative. Rosamund Pike, as the wife of one of the Ford execs his is nonetheless sympathetic to the cause gets the best speech in a film chock full of speeches, when she explains to Hawkins who her advanced degree from Cambridge somehow doesn’t keep her husband from treating her like she’s an idiot. Cinematically, the film isn’t much to look at. The draw here are the big performances and lefty reassurances.

My Film and My Story – At the opposite end of the budget and profile level is this student group project from Korea. Seven different kids at Konkuk University each directed one segment of this film about workers at a single-screen movie theatre on campus. The theatre is in the final stages of renovation before reopening (assuming they can win the support of the government), and the newly hired staff and strange customers have a series of mostly comical adventures. Two guys watch Happy Together and start to question their sexuality, a girl vehemently rebuffs the advances of a kid who talks about Lacan, another girl collects ticket stubs and nitpicks the temperature, but sleeps through the film and so on. It all looks quite polished (with only one sequence standing out narratively and visually from the whole, its placement at the film’s midpoint is certainly intentional), though the sound is a little rough at times. Best of all the sequences is one involving the manager of the theatre as she talks to her bartender about the cinema and why she loves it. It’s not as ambitious as Tsai Ming-liang’s Goodbye, Dragon Inn, but it is more grounded in reality and the day-to-day life of the people who actually work in theatres, which doesn’t make for a transcendent film-going experience, but certainly a pleasant one.