Movie Roundup: Hoping Karma Punishes the Colts Edition

You, the Living – I’ve tried a few times in the week since I saw this Roy Andersson film to describe what it’s about and have found myself wholly unequal to that task. It’s 50 short segments about the loosely interconnected lives of people living in an Ikea commercial world (pale, normal- (as opposed to movie-)looking people, flat, shadowless lighting, boxiness). Some of them want desperately to be understood, or communicate, or fall in love, or play music, though they may very well not be interested in applying any effort towards these goals. There are fantasies of houses that move like trains, B-52 bombers that may very well be real and always the sounds of Dixieland Jazz. It’s beautiful, despite its total lack of aestheticism, funny and sad, and always humane. The #4 film of 2007.

Bright Star – Like The Young Victoria, the other romantic biopic of 2009, it’s a better film than you think it would be. Abbie Cornish is very good as the girl in love with John Keats (played by Ben Whishaw, in a performance just as good, if not better, than Cornish’s). There’s not much surprising plot wise: the young lovers are kept apart, first by misunderstanding, then by society, and finally allowed to come together, though we know it’s too late. The exceptional thing about the film is its cinematography; director Jane Campion and DP Greig Fraser (this is the first I’ve seen of his work) apply every kind of light you can think of to their compositions: candlelight, lamplight, bright sunlight, magic hour twilight, icy winter light, smoggy London light, etc etc and the results are stunning. Pictorialism isn’t often a virtue, but here it works as a nice analogue to the romanticism of Keats’s poetry and the ways he explains the experience of it to Cornish as something that should be felt first and foremost through the senses.

Humpday – Raises an interesting question: does a totally stupid premise for a film become less objectionable if, at the end of the film, the characters realize how stupid they’re being? Does it create a bit of poignancy as we witness these characters, who we’ve reviled for their idiocy for much of the previous hour and fifteen minutes, come to the realization that they’ve been wasting their time, that they actually have nothing to say and nothing to show for their lives? Or is it just irritating that we’ve been subjected to this with the filmmakers knowing full-well how lame their central plot is? I’m on the fence. What I’m certain about, though, is that the direction by Seattle’s own Lynn Shelton is infuriating. She frames every shot, every shot, in close up, her hand-held, constantly moving verité camera wedged right up under her actors noses as if she wants us to count their pores. The effect is suffocating. And not in a way that analogizes the stifling nature of modern yuppie life. In a way that makes you want to scream “Stand back!” at the screen. The film does capture Seattle really well though. The houses are clearly Seattle houses. The people, all of them, talk like Seattle people. The festival that gives the main characters their lame idea is a real Seattle thing too. A friend of mine has had films there for the last several festivals. I don’t think he views it as a grand artistic attempt to justify his existence though. He just likes making porn cartoons. He’s weird.

Tulpan – A much better use of the same core concept (not the porn part, the escaping one world and trying for another world part) is this film from Kazakhstan and director Sergei Dvortsevoy. A young man, a former sailor in the Russian (I think) navy is trying to be a shepherd. It’s his dream to live a nomadic existence on the Steppe like his ancestors. He’s living with his sister’s family and trying to learn the business from his brother-in-law, who unfortunately thinks he’s useless. The local landowner won’t give him a flock or yurt of his own until he gets married (it’s a kind of sharecropper system), and the only unmarried girl for hundreds of miles thinks his ears are funny. And for some reason, all the baby sheep are dying. That’s pretty much it for plot, the film immerses you in its environment (dusty, windy and strangely beautiful) and characters (beautiful as well). There are plenty of stunning images (one of an approaching thunderstorm stands out in the memory), but it feels almost like they occur by accident, or are merely a fact of nature as opposed to images created by humans. The #13 film of 2008.

Still Walking – It’s A Christmas Tale à la Yasujiro Ozu. Koreeda Hirokazu’s film is about a family reuniting for the 15th anniversary of the oldest son’s death. He’d drowned while pulling a kid out of the ocean. There’s lots of food being cooked, family issues being glossed over and not resolved, more than enough passive aggression to go around and always a palpable sense of a family that loves each other, though they may not particularly like each other. The whole cast is great, but the real standout is Kirin Kiki as the mother. Koreeda films the family’s mostly traditional Japanese home much like Ozu would have, though he’s not nearly as strenuously stylized. The camera spends much of the time at tatami level, but occasionally rises to a traditional height. So it isn’t as rigorous an homage as, say, Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Café Lumière, but the music is definitely Ozuvian and the family dynamic almost seems like a reverse Ozu: in most of his films the family actually likes each other and keeps what issues they might have hidden. An interesting point of comparison is with Tokyo Story, wherein the parents are unwanted or ignored by their children. In Still Walking, it often seems to be the other way around. The #8 film of 2008.

![]()

Avatar – Well, the spectacle of it was fun, I’m a sucker for big battle scenes and I couldn’t help but get caught up in these. But it would have been better if it had cut out about 90% of the dialogue. I think it’s weird that the humans in the film had never seen Dances With Wolves. Or had any idea of their own history. Seems to me that the history of the last half of the 20th Century has relegated this kind of naked imperialism to the status of historical relic. Modern imperialists are much subtler, and you’d expect them to be even more so 150 years from now (unless of course, the leftward course of history continues and something like this never happens again). Of course, if it’s supposed to be a historical allegory, then its deviations from and simplification of the history of colonization in America are pretty glaring (it was about a lot more than naked greed for strip mining: international prestige and power politics, homes and land for a growing mass of poor people, often refugees from war-torn and even more poverty-stricken nations, evangelical religious imperatives, etc). Enough to render its critique kinda silly. The film has a couple potentially interesting ideas (the fact that everyone in it has an avatar: the humans’ are technological, the Na’vi are biological and the relation of the Na’vi’s electro-chemical connection with the plants and animals on their planet being analogous to what we’d call god) that don’t really get explored in favor of lame stereotypes of bloodthirsty soldiers (almost offensive, really) and Giovanni Ribisi’s half-assed Paul Reiser impression.

Movie Roundup: One Week Til Swing Time Edition

Love in the Afternoon – This is, apparently, a lot of people’s favorite of the Moral Tales, but I think I liked it the least. Part of my problem with it, though, is pretty silly: it has, by far, the worst clothing I’ve seen in a film in a very long time. I know 1972 was an awful time for fashion, but still, this is ridiculous. Sure, it’s kind of cute that the main character, a businessman (Bernard Verley) who has a platonic affair with an old friend (Chloe as played by Zouzou in some really horrifying outfits) while his wife is pregnant, wears nothing but turtlenecks (blue, red, lime green), except when he buys a tight flannel shirt right before meeting Chloe (symbolism!). The best part of the film happens early on, when Verley fantasizes about being able to control the minds of everywoman he meets, and all the ones he meets are the women from the other Moral Tales. A nice little touch tying them all together. This is the only of the Moral Tales wherein the protagonist is already married, in each of the others he’s only in love with or engaged to another woman when faced with temptation. That makes him a bit more reprehensible and also makes the film more conventional: from a relaxed exploration of the male psyche as it tries (and usually fails) to relate to and understand women, it becomes a critique of the banality of bourgeois life. After the other five films in the series, I expect more from Rohmer. The #9 film of 1972.

That Hamilton Woman – Vivien Leigh stars as a lower class girl who sleeps her way up the ranks until she gets to marry the British Ambassador to Naples during the Napoleonic Wars. Then, she meets Laurence Olivier’s Horatio Nelson (famous sea captain, also married) and falls in love. The two carry on their affair, regardless of the fact that everyone knows about it, because the two of them are so pretty that they just can’t keep their hands off each other. It’s essentially the real-life story of Leigh and Olivier’s relationship, except in reality Olivier kept all his arms and eyes. The two of them are as terrific as ever, and wonderful together. The #8 film of 1941.

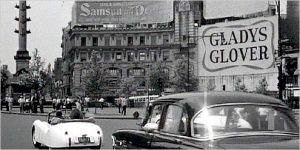

It Should Happen To You – I saw this 1954 George Cukor film on TCM, which showed it in the 1.85 aspect ratio. I looked around the internet and couldn’t find anything definitive on whether that’s the correct ratio or not. It looks like it may have been cropped at the top and bottom at times. Regardless, it’s an excellent comedy with Judy Holliday as a young woman who wants to be famous so much she buys a billboard and puts her name on it. It works and soon she’s a hit in ads and talk shows and is fighting off Peter Lawford. This bodes ill for her relationship with documentarian Jack Lemmon, whose interested in reality, not celebrity. Cukor and Lawford do some great work in the scene following his and Hollidays first date, with Lawford falling out of and suddenly imposing himself back into the frame next to her as she tries to say goodnight to him and get into her apartment alone, menacing and comical at the same time, it’s a textbook case of the power of blocking to carry a scene. The #15 film of 1954.

I Love Melvin – Another celebrity-seeking girl from the early 50s is Debbie Reynolds in this musical by director Don Weis (The Affairs of Dobie Gillis). The draw is the reuniting of Reynolds with her Singin’ in the Rain costar Donald O’Connor (who seems a bit out of place as the romantic lead, but that’s all part of the film’s charm). Reynolds plays an aspiring actress (she plays the football in a Broadway musical) and O’Connor a photographer’s assistant at Look magazine who falls for her. He promises to get her a spread, or a cover in the magazine in order to impress her family so they won’t make her marry some rich zero. Many songs ensue. And I mean it: it feels like this movie has more songs per minute than any musical I’ve ever seen. They’re not particularly famous songs, but they’re well-written and the dance numbers are terrific (chock full of references to other musicals too: O’Connor does a few Kellys (including the lightpost pose from Singin’ in the Rain) and Astaires (the rollerskates number from Shall We Dance). It all adds up to a perfect bit of fluff. The #10 film of 1953.

Movie Roundup: Finished Ulysses Edition

Claire’s Knee – The fifth of Eric Rohmer’s Six Moral Tales, it’s a kind of mellow version of Dangerous Liaisons. Jean-Claude Brialy (from A Woman Is A Woman, though now with an awesome beard) is on vacation at Lake Annecy (which is, like the beach house in La Collectionneuse, a stunning location and definitely a place I’d rather be). He’s about to move to Sweden to get married, when he meets an old friend who eggs him into a flirtatious relationship with a local teenaged girl. He than falls more seriously for the girl’s older sister, or more specifically, certain parts of her. Like the protagonists of most of the Moral Tales, Brialy isn’t a particularly admirable character, but he nonetheless remains both likable and sympathetic. This seems to be something special Rohmer brings to the films, maybe it’s in the leisurely pace, the dialogue and narration-heavy scripts, the visual relations between the characters and their environments, or just something basically decent and humanistic about the way he sees the world. He’s ever curious about behavior, and the lengths people go to to justify that behavior, but he never condemns and encourages that magnanimity in his audience. I can’t ever imagine feeling bad after watching a Rohmer movie. The #2 film of 1970.

It’s really hard not to compare this to An Education, a film with a similar subject, albeit with a different point of view: that of the young girl in a relationship with an older man. Despite that shift, though, the two girls in Claire’s Knee are much more interesting and real than the girl in the newer film, and where Claire’s Knee overflows with generosity and warmth, An Education is bitterness and cynicism, its characters existing, for the most part as cheap jokes or object lessons.

Fixed Bayonets! – Samuel Fuller’s second Korean War film from 1951, it’s not nearly as good as the first, The Steel Helmet. Still, it’s a rock solid movie, a kind of version of the Battle of Thermopylae with a single platoon of 48 men left to hold a mountain pass against the Chinese while the rest of their division retreats. The heart of the movie rests with a corporal played by Richard Basehart who doesn’t want to be a leader because he fears sending men to their death. The film is structured around the deaths of the four men who outrank him, leaving him at the climax to face his fears and lead his remaining men to complete their mission. As always, Fuller is grittier than the mainstream, but the whole thing feels a bit too schematic and doesn’t ever reach the poetic heights of his best films. The #17 film of 1951.

Looney Tunes: Back in Action – Way better than you think it would be. Brendan Fraser stars as a stuntman who gets mixed up with the recently fired Daffy Duck. The two of them take off on an adventure after Fraser’s father (Timothy Dalton) an actor who stars in James Bondish spy movies as a cover for his secret life as a spy. Dalton’s been kidnapped by the head of the Acme Corporation (Steve Martin, in possibly his worst ever performance) for something to do with some kind of jewel that turns people into monkeys. As Fraser and Daffy try to rescue him, their joined by Bugs Bunny and Jenna Elfman (also pretty terrible as the executive who fired Daffy, sent to rehire him). Director Joe Dante’s achievement here is that he truly captures the anarchic spirit of the Looney Tunes cartoons. There are jokes aplenty (visual, verbal, Hollywood satirical) some of them not funny at all, like Steve Martin’s whole performance, but the rapid-fire pace never slows down. The #18 film of 2003.

Mission To Moscow – Part of the series TCM’s been running this month on depictions of Russia in American film, this one is truly weird. At the height of World War II, the Roosevelt government encouraged Warner Brothers to make this adaptation of the memoir of the American Ambassador to the Soviet Union in the late 1930s, Joseph Davies. Michael Curtiz directs (it was his follow-up to Casablanca) and the film seems oddly split. On the one hand, it does a yeoman’s job of whitewashing the real concerns Americans had about Stalin’s government (the show trials, the lack of industrial progress, the failures of the 5 Year Plans), but on the other, the film seems to covertly acknowledge that those fears are real. More striking is a show trial sequence, when a number of Soviet officials (all of whom we’d met in the first half of the movie) are put on trial for plotting a Trotskyite coup against Stalin. The trials consist almost exclusively of confessions (which with historical hindsight we can assume were forced), and Davies is there to assuage any doubts as to their veracity. Someone even asks him “How can we be sure these confessions are real?” To which he responds “I’ve been a trial lawyer for 30 years: they’re real.” Now, either he’s the worst lawyer ever, or he’s lying for the sake of propaganda. I think he’s lying and I think Curtiz knows it. It shows in the way he directs the performances of the people on trial. I think. Maybe it just looks that way 60 years into the future. I’d love to know what audiences thought of this film when it was released. The #16 film of 1943.

Movie Roundup: MLK Day Edition

Suzanne’s Career – The second of Eric Rohmer’s Six Moral Tales, and much darker in tone than The Bakery Girl of Monceau. It feels kind of like what would happen if the guys from Metropolitan tried to act like the jerks from In the Company of Men. A caddy young man dates a girl he doesn’t really like. His friend (who seems to be a bit in love with the guy) really doesn’t like the girl either, but considers dating her as well. The girl, seen exclusively from the boys’ perspective, is a bit of a cipher. In the end, though, we see that Rohmer was totally on her side all along. The black and white cinematography has a really cool shadowyness to it during the many party sequences. The #15 film of 1963.

My Night at Maud’s – Moral Tales, Part III, this time feature length with some great acting from Jean-Louis Trintignant (Three Colors: Red) and cinematography by Nestor Almendros (Days of Heaven). Trinignant plays an engineer in his early 30s (this is the first of the Moral Tales not about students) who’s trying to be Catholic and has some issues with Pascal. He’s in love with (but has never talked to) a pretty blonde he’s seen at Mass. He meets an old school buddy who drags him along to meet his girlfriend, the titular Maud, who interrogates him about his life and philosophy and kind of flirts with him. The bulk of the film is their conversation. All the Moral Tales have essentially the same plot, but differ in the kinds of characters they present the dilemma of fidelity to. The is the first one wherein every character is truly lovable (the guys in the first two are pretty much jerks, Trintignant here isn’t perfect (he’s actually kind clueless) but adorably so). The #2 film of 1969.

La Collectionneuse – Moral Tales, Part IV and a step backward in the likability department. The Almendros photography is in color this time, and he really captures the beauty of the film’s Riviera location. Two guys stay at their friend’s vacation house for a month, along with a girl neither of them knows but who seems kind of slutty. They make a kind of game out of competing for her without acknowledging they actually like her. Their behavior is, for the most part, detestable, but at least seems to know that and enjoys playing along for her own entertainment. The ending, which is pretty much perfect, makes me love the film a lot more than I did while watching it. I too want to spend my time at an awesome house on the ocean trying my best to do absolutely nothing. The #15 film of 1967.

In the Loop – Pretty much as advertised: hilarious, with some great performances, especially by Peter Capaldi. It’s a screwball farce about the lead up to war in Britain and the US, kind of The West Wing meets Arrested Development, with, yes, a little Mamet thrown in. Based on a TV series, and I can see it working a lot better in that format, as none of the characters are really developed. In the end, the fact that the film follows so closely what actually happened in the lead-up to the Iraq War moves it from good fun to horribly depressing. Up until then, it’s the funniest movie of the year.

The Hurt Locker – Another highly acclaimed 2009 movie that succeeded in meeting my lofty expectations. Director Kathryn Bigelow’s action sequences are as well-constructed and filmed as their reputed to be: they show a palpable sense of geography and a really patience with the building of suspense. Jeremy Renner and Anthony Mackie are terrific as bomb squad soldiers in Baghdad, though the film kind of falls apart whenever it’s attempting to build them into characters, especially with Renner’s character. The film seems to want him to be a crazy adrenaline junkie to is wild, takes risks and can’t handle life on the outside. But Renner plays him more subtly, more as a man who doesn’t love war, but instead has found it’s the only place he feels at home. He doesn’t need a rush, he needs to be a hero. Regardless, the action sequences alone are enough to make it a great film. The #10 film of 2008.

Movie Roundup: Eating with Relish the Inner Organs Edition

An Education– I’d expect that a film about a young girl in 1962 who’s so infatuated with the life of the Parisian intellectual (jazz, cigarettes, New Wave movies) that she dates an older man to have at least a sense of why that Parisian lifestyle is so interesting. Or a sense that the guy she’s dating as cool or exciting or smart or dangerous or something. But everything in this movie is tame: the affair is about as passionless as it can get, even for the English; the guy is pretty boring – more traveling salesman than transgressive cad; and the film itself is written and shot so tastefully as to be pretty much inert. The actors are good though: Carey Mulligan doing that clever waif thing that’s worked for actresses from Audrey Hepburn to Natalie Portman, Olivia Williams and Emma Thompson as teachers who for some reason can’t explain why they like teaching (it’d be inconvenient for the plot or something, I guess), and Alfred Molina as the father. He gets the best scene in the film: his little speech near the end. It’s the only really moving thing in the whole film.

College – Possibly my least favorite Buster Keaton feature. I’m actually liking The Freshman more in comparison. Keaton plays a geek who goes to college and decides the girl he loves want him to be an athlete. The film then plays as Keaton tries (and fails) to play various sports: baseball (with one of my favorite players, HOFer Wahoo Sam Crawford in his only film role), track and field, rowing. It’s much funnier than the Lloyd film, of course, as Keaton’s just a better physical comedian. But it has none of the emotional depth that Lloyd, despite the fact that I was so bored with most of his film, managed to create. The #7 film of 1927.

Dragon Inn – The third King Hu kung fu film I’ve seen, and it’s somewhere in-between the other two ambition-wise. Come Drink With Me, while pretty great for the first two-thirds, was marred by an imposed ending from the Shaw Brothers, with cheap and rather silly special effects. A Touch of Zen, on the other hand, is a vast epic, something that’s aspiring to be the Seven Samurai of the kung fu genre (and comes very close to succeeding). This one isn’t quite that ambitious, and more successfully maintains its tone through the entire film. The plot is an archetypal one: good guys and bad guys converge at a remote location, beat each other up. The action is pretty much perfect, a difficult task without any performers as virtuosic as Gordon Liu or Jackie Chan, but one Hu manages through framing and perfectly-timed editing. The #5 film of 1967.

The Scarlet Empress – The fifth collaboration between Josef von Sternberg and Marlene Dietrich I’ve seen, and it might be the craziest and the most fun. Dietrich plays the young Catherine the Great, in her rise to Tsarinadom. The early plot, in fact, is suspiciously like that of Sofia Coppola’s Marie Antoinette. Dietrich plays a young German girl brought to Russia to marry the heir to the throne, who is, of course, a lunatic. She freaks out, learns to scheme and manipulate and eventually stages a coup that puts her in power (with the help of the army, large parts of the command of which she appears to have slept with). Dietrich’s pretty funny working against type as the innocent waif in the beginning, and of course she owns the double entendres at the end. The best thing about the film though is the set design: the Kremlin as a kind of Gothic horror show with oversized statues of demons and agonized saints everywhere: walls, bannisters, tabletops, as chairs, etc. The #5 film of 1934.

Madame Bovary – Vincente Minnelli’s version of of the Flaubert classic is told with a weird framing device. Flaubert is on trial for writing the book (corruption of public morals, in that it expects us to sympathize with the greedy adulterous title character) and as a defense tells the story of the novel. Thus we have the author (in the form of James Mason, of all people) narrating the action as if it were a kind of argument: the story exists to make us feel sympathy for Emma Bovary. It reduces the novel from one of romance and melodrama to one of social argument, which is far less interesting. Anyway, jennifer Jones plays Emma and is pretty good (she looks like a softer, rounder Vivien Leigh). The standout sequence, one of the very best of Minnelli’s career is the ball sequence. I’ve never seen a 19th century dance filmed with such speed, both with the dancers and the camera (when it follows the spinning waltzers). It’s a breathtaking sequence, and when the windows are smashed open to let in some air, you’re glad for it as well. The #13 film of 1949.

A Serious Man – I finally managed to see this, the new Coen Brothers film. It’s very much of a piece with their Barton Fink, both revolving around protagonists that don’t understand what’s happening around them mostly because they just don’t listen. Michael Stuhlbarg is quite good as Larry Gopnick, a physics professor (Schrödinger’s cat & the Uncertainly Principle, of course) who learns his wife wants a divorce, he might not get tenure, he’s being sued for accusing a student of trying to bribe him. And that’s just the first act. More disasters await Larry as he desperately tries to find answers to why all these things are happening to him. He makes several trips to several rabbis, all of whom give him the same, essential existential answer: we don’t know, try to enjoy life and be a nice person. That’s not enough for Larry, he needs to know: what is God’s plan, do actions have consequences? The film exists in an in-between state in whether we’re supposed to believe the actions we see are random or determined by God; like Schrödinger’s cat, both possibilities are true for the duration of the film. Until, that is, Larry makes a choice. Then all the possibilities collapse into one, and it doesn’t appear to be a happy one.

Party Girl – A really solid gangster melodrama from director Nicholas Ray. Cyd Charisse plays a titular showgirl who falls for Robert Taylor’s crippled mob lawyer (he makes his living defending Prohibition Era hoods in the employ of Lee J. Cobb in 1920s Chicago). They help each other become better people, which inevitably puts them in conflict with the gangsters. Shootouts and nobility ensue (including a montage of whackings that must have inspired Coppola’s [i]The Godfather[/i] in some way). This being a 50s melodrama, there’s even the obligatory miracle surgery. Charisse gets a couple of great musical numbers (just dancing), though they’re marred by some terrible outfits, by the end, she completely wins you over (and not just with her legs, despite Ray’s impressive singularity of focus on them). Above all, the film is notable as yet another Ray film with deeply drawn, very damaged characters struggling against life, despite all the generic clutter than threatens to take over: that powerful emotional undercurrent keeps things (like Lee J. Cobb) from degenerating into farce). The #10 film of 1958.

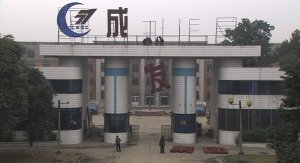

24 City – The latest (available) feature from Jia Zhangke is the story of a factory closing in the industrial town of Chengdu. It’s told through a series of nine interviews, five of which are actual people telling their story, four are actors telling composite stories compiled from among the 130+ people Jia interviewed for the project. The conceit is made clear from the opening credits, which cite famous actresses Joan Chen and Zhao Tao. Far from feeling dishonest, however, the act is consistent with the way Jia’s latest films have mixed reality and unreality (The World‘s animated interludes and surreal setting; Still Life‘s alien artifacts imbuing a desolate, dismantled town with enough humor and romance to keep things from getting to boring or depressing). The film is shot digitally, with lovely slow pans over the factory (the last workers at work, things been torn down and taken apart, workers leaving the factory in what is probably a Lumière homage). The version I saw on the Instant Netflix and a weird ripple in the image every time the camera panned. I don’t think that was intentional. The #4 film of 2008.

The Bakery Girl of Monceau – The first of Eric Rohmer’s Six Moral Tales is a short film about a law student (future director Barbet Schroeder, with voiceover narration by future director Bertrand Tavernier) who sees a pretty woman walk by every day, over-thinks a plan to ask her out, and ends up buying cookies every day waiting to run into the girl again. He flirts with the bakery girl (for various potential reasons) and drops her when the first girl returns. It definitely feels like there’s more of a movie in this story, something that could have run for 90 instead of 23 minutes. On the other hand, it’s pretty much perfect as it is. Schroeder’s attention to habit, his circular, obsessive logic and ultimate callousness feels very true to life. The #11 film of 1963.