Here are reviews of the two separately released parts of The Crossing. We talked about John Woo’s career in general on They Shot Pictures a few months ago.

The Crossing – reviewed August 13, 2015

The first part of John Woo’s latest epic (the second part was recently released in China to little fanfare, but isn’t available here yet) is a romantic war movie in the style of The Big Parade or Doctor Zhivago, with a half dozen characters caught up in the Chinese civil war following the defeat of the Japanese in 1945. The most direct connection is probably Cai Chusheng and Zheng Junli’s 1947 film The Spring River Flows East which follows the ups and downs of a family awash in the same history, and was also released separately in two parts.

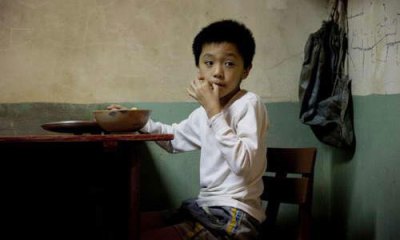

Leaving the nautical disaster that’s led the project to be dubbed “John Woo’s Titanic” for the second half, this first part follows the three major stars and their satellite characters through the civil war: Zhang Ziyi as an illiterate nurse trying to get by while searching for the man she loves (a soldier), Takeshi Kaneshiro as a Taiwanese doctor who has lost the woman he loves (a Japanese girl), and Huang Xiaoming as a Nationalist general who falls in love with and marries a young woman before shipping her to safety in Taiwan (where she lives in Kaneshiro’s girlfriend’s old house). It’s lush and romantic (a quite pretty score by Taro Iwashiro, who also did the stirring and lovely music for Woo’s Red Cliff), with golden hues, wind blowing through grasslands, pointed freeze frames and slow motion (yes, and doves), balanced by the horrors of war: starving children, students and dancing girls beaten in the streets, freezing trenches and explosive heroism. Nobody mixes action and melodrama with more seriousness than John Woo.

One person’s old fashioned and sappy is another person’s classical and heartfelt. And I am nothing if not a sucker.

The Crossing II – reviewed December 2, 2015

Such a strange movie, less a continuation of the story of Part One than a partial remake of it (pointedly perhaps its title is “The Crossing II” and not “The Crossing Part II“), as the first half hour not only recapitulates what went before, but completely replays whole scenes with slightly different editing and a few extra scenes added in. The next hour or so continues the rhythm of the first film, intercutting between the various leads as they all slowly make their way to the doomed boat (a title card at the opening gives us all the details of the impending disaster, with some of this information to be repeated verbatim at the end of the film). The emphasis is on Takeshi Kaneshiro’s doctor, first in his friendship with Song Hye-kyo (the wife of Nationalist general Huang Xiaoming), then with his family (ostensibly his younger brother who wants to run off from Taiwan to Shanghai to become a prostitute, but as it plays the relationship is more with his mother and sister-in-law (his older brother’s widow), who is played by Woo’s daughter Angeles), and finally, on the boat, with Zhang Ziyi, the idealistic young woman willing to do anything up to and including prostitution in her quest to survive long enough to find the army man she loves (“When I believe someone, I believe him whole-heartedly. Shouldn’t it be that way?” she says, in a line that does much to summarize Woo’s entire career).

Recentering the film in this manner makes it less an ensemble piece about love in a time of war, as the first one is, than a film about the endurance of women in the face of tragedy. Perhaps this is the influence of Tsui Hark, brought in at the last minute to help assemble the final cut of this film. The whole thing feels like it was hastily assembled in response to the box office failure of the first film. I’m very curious how the second half was to play out in its initial conception, as I quite liked Part One, it had the sweep and loveliness of a great historical melodrama, like Woo’s version of the great 1947 Shanghai film The Spring River Flows East. The second part though would probably play better, or at least just as well, as a single film, in isolation from the first. The jumbling repetitions of the first film irreparably break the rhythm, we’re left wondering why we’re seeing these scenes again, and why the new scenes were deleted from the first film, rather than being caught up in the emotions on-screen.

For all its billing, this is not “John Woo’s Titanic“. In its loveliness, deep anxiety about the past and the horrors of history (one of the many fascinating things about it’s look at the Civil War is that both sides are pretty much equally terrible, while good people populate the ranks of both armies), breathtaking romanticism and flights of digital expressionism, this is nothing less (and nothing more) than John Woo’s War Horse.